All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Relationship between Aspirin Resistance and Gene Polymorphism in Chinese Patients with Cerebral Infarction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

Introduction

Ischemic stroke, a major subtype of cerebral infarction, results from reduced blood flow to the brain and presents various neurological dysfunctions. Ischemic stroke incidence remains high both globally and in China. Due to its antiplatelet aggregation properties, aspirin is widely used and has been shown to reduce the risk of stroke. However, some patients develop Aspirin Resistance (AR), particularly after recurrent cerebral infarction. This study conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to examine the association between genetic polymorphism and AR in ischemic stroke.

Methods

A comprehensive literature search was conducted from October to December 2024 using PubMed, Web of Science, and Embase to identify relevant studies on AR and genetic polymorphisms in Chinese populations. Eight studies, encompassing a total of 2,951 participants and published between 2014 and 2024, met the inclusion criteria.

Results

The meta-analysis identified five genetic polymorphisms that are significantly correlated with the resistance response of patients with cerebral infarction to aspirin: Cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1), Prostaglandin-Endoperoxide Synthase 1 (PTGS1), Platelet Endothelial Aggregation Receptor 1 (PEAR1), ATP-Binding Cassette Sub-familyB Member 1 (ABCB1), and P2Y1 Receptor (P2RY1). The overall Odds Ratio (OR) was 11.56 (95% CI: 2.45–54.62), p = 0.002, indicating a strong association between these polymorphisms and AR. OR refer to the allele contrast (dominant vs. wild-type model).

Discussion

This meta-analysis evaluated the association between genetic polymorphisms and AR in Chinese people, particularly those involving PEAR1, PTGS1, COX-1, ABCB1, and P2Y12.

Conclusion

This systematic review and meta-analysis indicate that genetic polymorphisms - especially COX-1, PTGS1, PEAR1, P2Y1, and ABCB1 may play an important role in the development of AR and influence ischemic stroke outcomes in the Chinese population.

1. INTRODUCTION

Stroke is the second leading cause of death in the world, with about 13.4 million cases each year. In China alone, the incidence is particularly high, with 1,114.8 cases per 100,000 people [1]. There is a reciprocal relationship between disability rate and significantly impairing patients’ quality of life [2]. With an aging population and evolving social and environmental conditions, the incidence of stroke is expected to rise steadily [3].

Ischemic strokes account for roughly 85% of all stroke cases and are characterized by heterogeneous thrombotic and embolic occlusions composed primarily of fibrin, red blood cells, and platelets. Low-dose aspirin (100–200 mg daily) is commonly recommended for both the treatment and prevention of ischemic stroke due to its antiplatelet properties [4]. Aspirin exerts its effect by inhibiting Cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1), which in turn reduces the production of Thromboxane A2 (TXA2), thereby inhibiting platelet aggregation [5]. However, the efficacy of aspirin varies among individuals due to differences in COX-1 and TXA2 activity. Notably, AR can develop in certain ischemic stroke patients. AR can be classified into laboratory and clinical types [6]. Laboratory AR refers to the failure of aspirin to reduce TXA2 production despite COX-1 inhibition, resulting in continued platelet activation and aggregation [7]. On the other hand, in clinical practice, AR is when the occurrence of ischemia occurs despite taking aspirin for a long time.

The prognosis varies between 5% and 65% depending on the patient group and the methods and expertise used to measure blood cell function [8-14]. For instance, Derle [15] utilized a platelet function analyzer to evaluate 208 stroke patients and reported an incidence of 32.2%. In contrast, a study by Jing Y [16] using the Verify Now assay found a lower incidence of 19.7% among 196 patients.

Although the exact mechanisms underlying AR remain unclear, several contributing factors have been identified, including metabolic disorders, poor medication adherence, reduced drug bioavailability, drug-drug interactions, and genetic polymorphisms. The aim of this review is to investigate genetic polymorphisms and their relationship to AR in the Chinese population. By identifying relevant genetic factors, this review seeks to contribute to the advancement of personalized antiplatelet therapy strategies for the prevention of cerebral infarction.

2. METHODOLOGY

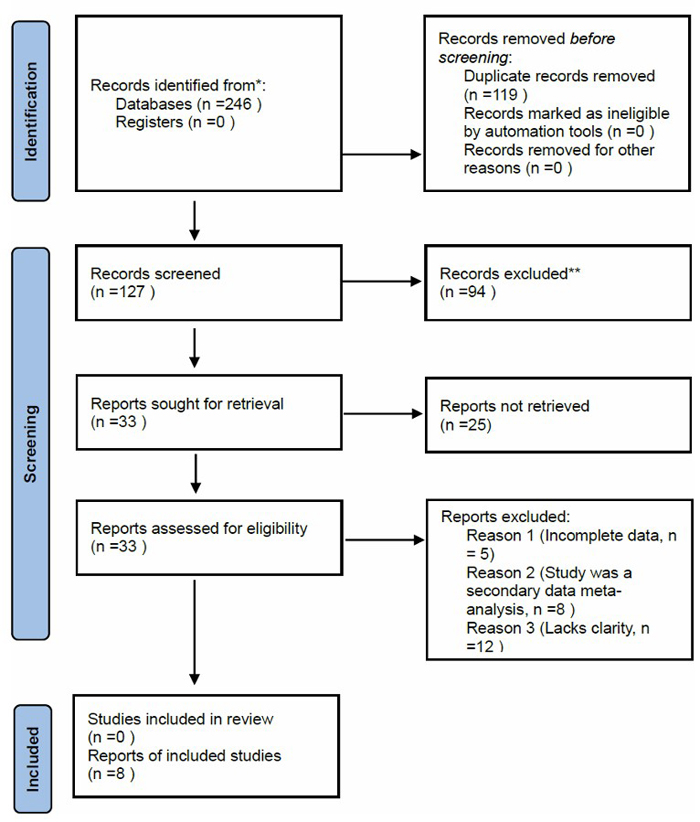

A comprehensive literature search was conducted from October to December 2024 using three major electronic databases, PubMed, Web of Science, and Embase, to identify studies investigating the association between genetic polymorphisms and AR in Chinese populations. All retrieved records were cross-referenced, and citations were verified to ensure completeness and relevance of the included literature. The study followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) framework, which provided a structured approach for screening and data selection (Fig. 1) [17]. Initially, 246 publications were identified. After removing 119 duplicates and 127 irrelevant records based on title and abstract screening, 33 articles remained for detailed review. Following a full-text assessment using predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria, eight studies were included in the systematic review.

An objective risk of bias assessment was conducted using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist [18]. The qualitative evaluation was carried out in accordance with the local research context. Specifically, the CASP checklist for cross-sectional studies was employed to systematically appraise the methodological quality and credibility of each included article.

2.1. Selection Benchmarks

Studies were included based on the following criteria: i) The experimental design was either a case-control study or a cohort study, ii) Participants were confirmed ischemic stroke patients from China, iii) The study investigated genetic polymorphisms associated with AR, iv) The articles were published in English, and v) The publication year ranged from 2014 to 2024. Exclusion criteria comprised: i) Conference abstracts, review articles, animal studies, and case reports, and ii) Studies with incomplete data or those from which data could not be extracted.

Relevant studies were identified using a comprehensive search strategy combining keywords and Boolean operators: (“Ischemic Stroke” OR “Cerebral Infarction”) AND “Aspirin Resistance” AND “Gene Polymorphism” AND (“Chinese” OR “China”). The Boolean operators were applied to optimize both the sensitivity and specificity of the search. Article selection was performed independently by the authors, and any disagreements were resolved by consensus via email discussion. After removing duplicate records, titles and abstracts were screened for relevance. Full-text articles that met the inclusion criteria were then retrieved and re-evaluated to ensure that only eligible studies were included in the final analysis.

2.2. Quality Assessment

The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used to assess the quality of the studies [19]. The NOS scale assesses the risk of bias in observational studies with three domains: i) selection of participants, ii) comparability, and iii) outcomes. A study could be given a maximum of one point for each numbered item within the selection and outcome areas, and a maximum of two points allocated for comparability. The NOS score ranges from zero to nine. A score of seven to nine indicates that the article is of high quality and has a low risk of bias, a score of four to six indicates good quality with a moderate risk of bias, and a score of zero to three indicates low quality and the highest risk of bias.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for study selection.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using RevMan version 5.3 software (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK). For continuous variables, the mean difference was used as the effect measure, whereas for dichotomous data, the Odds Ratio (OR) was used. Each effect size was presented with its 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Heterogeneity among studies was assessed using the Chi-square (χ2) test with α = 0.10, and its magnitude was quantified using the I2 statistic. When heterogeneity was low (I2 ≤ 50%), a fixed-effect model was applied; otherwise, a random-effects model was employed. In cases of substantial clinical or methodological heterogeneity, subgroup analyses or sensitivity analyses were conducted to explore potential sources of variability. Potential publication bias was evaluated visually using funnel plots. A two-tailed p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Characteristics of the Studies

The clinical characteristics of all studies are shown in Table 1. There are 2951 participants included in the study. Specifically, the recruited participants were from hospitals located in regions with overwhelmingly Han Chinese populations (Eastern, Central, and Northern China), where Han Chinese constitute over 95% of the total local population according to the latest national demographic data. The eight studies included five case-control studies and three cohort studies on gene polymorphisms, namely COX-1, PTGS1, PEAR1, ABCB1, and P2Y1.

| Study (Author, year) | Definition of AR | SNPs | AR | AS | Total | Mean Age (Years ± SD) | Vascular Risk Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cai H et al, 2017 [27] | Poor functional outcomes | PTGS1 | 145 | 472 | 617 | 58.72±12.06 | 1, 2 |

| Zhao J et al, 2019 [33] | Recurrent ischemic stroke | PEAR1 | 137 | 56 | 193 | 63.20±10.2 | 3, 4 |

| Zhang L et al, 2024 [28] | Recurrent ischemic stroke | PTGS1 | 116 | 92 | 208 | - | 5 |

| Cao L et al, 2014 [20] | Primary endpoint | COX-1 | 67 | 792 | 859 | 59.82±12.57 | 2, 6 |

| Xu L et al, 2022 [14] | The thrombelastogram and platelet aggregation test | ABCB1 | 77 | 225 | 302 | 64.51±11.56 | - |

| Lu SJ et al, 2016 [37] | Cerebral infarction group | P2Y1 | 50 | 297 | 347 | 62.87±12.06 | 1, 2 |

| Li Xg et al, 2018 [42] | Recurrent ischemic stroke | ABCB1 | 10 | 147 | 157 | - | - |

| Li Xq et al, 2016 [21] | Recurrent clinical events | COX-1 | 39 | 229 | 268 | 62.96±8.99 | - |

Note: AR = Aspirin resistance, AS = Aspirin-sensitive; Vascular risk factors: 1 = Hypertension; 2 = smoking; 3 = lipid-lowering agents; 4 = LDL; 5 = BMI≥30; 6 = more than one previous stroke.

3.2. Quality Assessment

Table 2a summarizes the NOS assessment for the three cohort studies, while Table 2b presents the results for the five case–control studies. Among the case–control studies, one study obtained an NOS score of six points, indicating moderate quality, whereas five studies scored eight points and two studies scored nine points, both of which are considered high quality. Overall, most studies demonstrated strong methodological rigor and low risk of bias according to the NOS criteria. Across all studies, the selection domain generally achieved high scores, reflecting clear definitions of cases and controls, as well as representativeness of the study populations. The comparability domain varied among studies; most adjusted for major confounders such as age, sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and smoking status, although a few studies provided limited details on additional covariates. The exposure domain was consistently rated highly, as standardized diagnostic criteria and validated laboratory methods (such as platelet aggregation assays and genetic polymorphism analyses) were used in data collection.

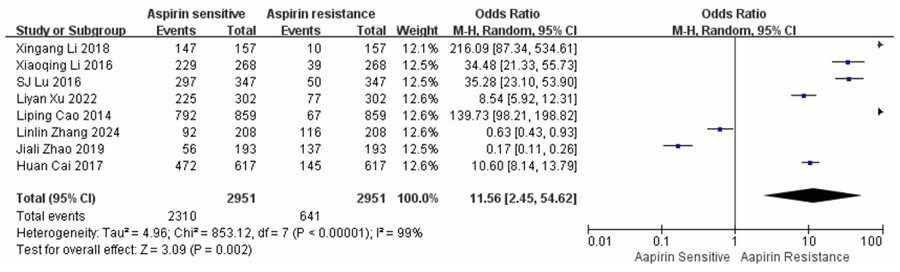

3.2.1. Comparison among AR and AS Groups

Approximately 20% of the participants were found to have AR. A meta-analysis of eight studies involving 2,951 participants comparing AR versus AS individuals yielded an overall OR of 11.56 (95% CI: 2.45–54.62); a significantly higher likelihood of adverse outcomes among AR individuals. Substantial heterogeneity was observed among the included studies (I2 = 99%, p < 0.001*), prompting the use of a random-effects model for the pooled estimation. As illustrated in Fig. (2), the overall effect was statistically significant (Z = 3.09, p = 0.002), indicating that AR is strongly associated with an increased risk of recurrent or poor clinical outcomes compared to AS individuals.

| Study (Author, year) | Selection | Comparability Outcome | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Representativeness of the Expose Cohort (*) | Selection of the Non-Exposed Cohort (*) | Ascertainment of Expose (1 point) | Demonstration that the outcome of interest was not present at the start of the study (*) | Comparability of Cohort based on the Design or Analysis (**) | Assessment of Outcome (*) | Was follow-up long enough for outcomes to occur (*) | Adequacy of Follow-Up Cohorts (*) | Quality Score | |

| Cai H., et al, 2017 [27] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 8 |

| Cao L., et al,2014 [20] | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | - | 8 |

| Xu L., et al, 2022 [14] | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * | 9 |

Note: Each asterisk (*) represents one point, and double asterisks (**) represent two points according to the NOS; Demonstration that outcome was not present at start of study = verified absence of stroke recurrence or aspirin resistance at baseline; Missing item (–) = not clearly described in study report; studies scoring ≥7 were considered high quality; scores of 6 indicate moderate quality.

| Study (Author, year) | Selection | Comparability Exposure | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case Identification is Appropriate (*) | Case Representation (*) | Contrast Selection (*) | Determination of Contrast (*) | The comparability of cases and controls was considered in the design and statistical analysis (**) | Identification of Exposure Factors (*) | The exposure factors of cases and controls were determined by the same method (*) | Nonresponse Rate (*) | Quality Score | |

| Zhang L., et al, 2024 [28] | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | - | 8 |

| Zhao J., et al, 2019 [33] | * | * | - | * | ** | * | * | * | 8 |

| Li Xg., et al, 2018 [42] | * | * | - | * | - | * | * | * | 6 |

| Li X Q., et al, 2016 [21] | * | * | - | * | ** | * | * | * | 8 |

| Lu S J., et al, 2016 [37] | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * | 9 |

Note: Each asterisk (*) represents one point, and double asterisks (**) represent two points according to the NOS; Missing item (–) = not clearly described in the study report; studies scoring ≥7 were considered high quality; scores of 6 indicate moderate quality.

A forest plot comparing AR and AS across eight studies.

3.2.2. Comparison among Case-control Studies: AR vs. AS

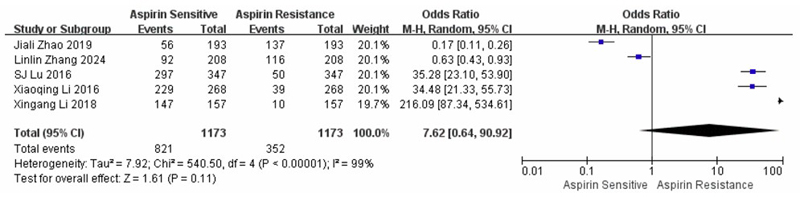

A meta-analysis of five case-control studies comparing AR and AS individuals, involving a total of 1,173 participants, including PEAR1, PTGS1, ABCB1, COX-1, and P2Y1, yielded an overall OR of 7.62 (95% CI: 0.64–90.92). Marked heterogeneity was observed among the included studies (I2 = 99%, p < 0.001), indicating substantial variation in effect estimates. Therefore, a random-effects model was applied. As shown in Fig. (3), the pooled estimate did not reach statistical significance (Z = 1.61, p = 0.11), suggesting that the association between genetic polymorphisms and AR was not statistically significant in this subgroup analysis.

Forest plot summarizing the five case-control studies comparing aspirin resistance and aspirin sensitivity.

3.2.3. Comparison among Cohort Studies: AR vs. AS

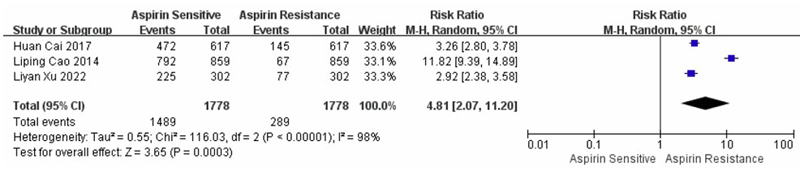

A meta-analysis of three cohort studies comparing AR and AS individuals, involving a total of 1,778 participants, examined PTGS1, ABCB1, and COX-1 and yielded an overall OR of 4.81 (95% CI: 2.07–11.20), indicating a higher risk of adverse outcomes among AR individuals. Significant heterogeneity was detected among the included studies (I2 = 98%, p < 0.001), suggesting substantial variability in effect estimates. Consequently, a random-effects model was employed. As illustrated in Fig. (4), the overall effect was statistically significant (Z = 3.65, p = 0.0003), demonstrating that AR was significantly associated with an increased likelihood of unfavourable clinical outcomes compared to AS participants.

Forest plot showing the results of three cohort studies comparing aspirin resistance and aspirin sensitivity.

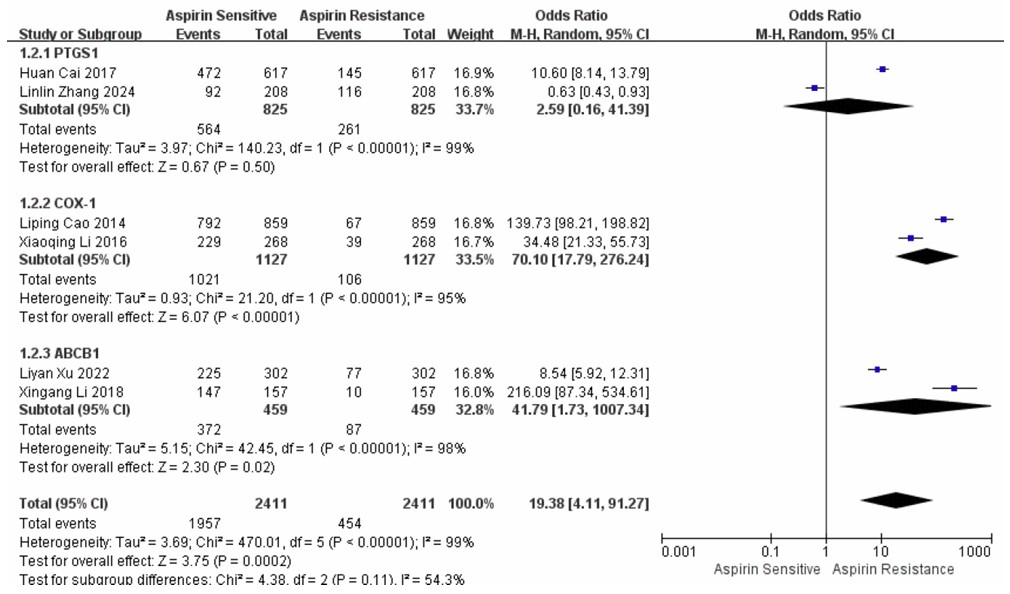

3.2.4. Subgroup Analysis: AR vs. AS by Genotype

To further evaluate genotype-specific associations with AR, subgroup analyses were conducted for the PTGS1, ABCB1, and COX-1 polymorphisms. For the ABCB1 genotype, three studies comprising a total of 459 participants yielded a pooled OR of 0.02 (95% CI: 0.00–0.58), with substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 98%, p < 0.001). The random-effects model revealed a statistically significant association (Z = 2.30, p = 0.02), suggesting that variations in the ABCB1 gene may influence the occurrence of AR. Analysis of the PTGS1 genotype, involving 852 participants, produced an overall OR of 0.39 (95% CI: 0.02–6.16) with high heterogeneity (I2 = 99%, p < 0.001). The association was not statistically significant (Z = 0.67, p = 0.50). In contrast, the COX-1 genotype analysis, based on 1,127 participants, demonstrated a strong association with AR (OR = 0.01, 95% CI: 0.00–0.06), accompanied by substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 95%, p < 0.001). The overall effect was highly significant (Z = 6.07, p < 0.00001), as shown in Fig. (5).

Forest plot showing the results of analyses comparing AR and AS across three distinct subgroups.

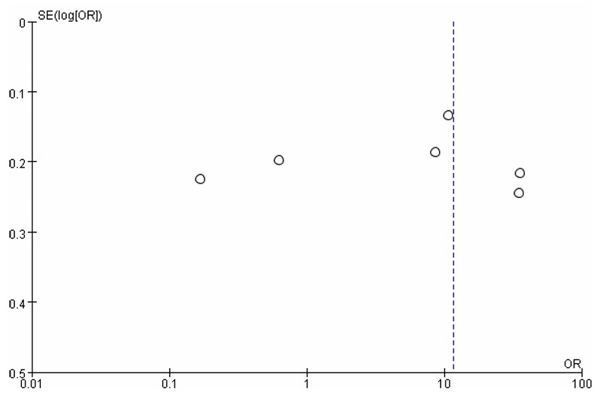

3.2.5. Funnel Plot

A funnel plot was constructed to assess potential publication bias among the included studies (Fig. 6). Visual inspection of the plot revealed an asymmetrical distribution of data points, suggesting publication bias. The scatter of studies was uneven around the pooled effect size, with several smaller studies deviating from the central line.

Funnel plot.

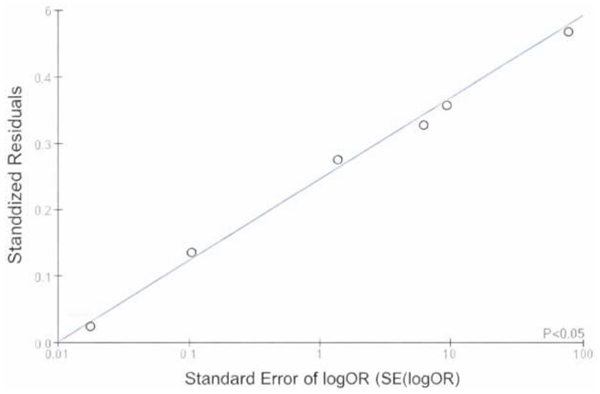

To further evaluate the presence of publication bias, Egger’s regression test was performed, and the results are illustrated in Fig. (7). The regression line demonstrates a positive intercept, indicating a potential asymmetry in the distribution of effect sizes. This asymmetry suggests the possibility of small-study effects or selective publication of studies with significant results. However, the observed trend did not reach statistical significance (p > 0.05).

Egger's regression plot.

4. DISCUSSION

Aspirin remains the cornerstone of antiplatelet therapy for the prevention of ischemic stroke, yet variability in individual response poses significant clinical challenges. Approximately 20% of patients in this meta-analysis exhibited AR, consistent with rates reported in prior global studies (15–25%). Genetic polymorphisms have increasingly been recognized as contributors to this variability, and our pooled analysis highlights significant associations between AR and variants in COX-1, PEAR1, PTGS1, ABCB1, and P2Y1 genes among Chinese ischemic stroke patients. This suggests that heritable factors substantially influence platelet reactivity and antiplatelet efficacy in the Chinese population.

The overall pooled OR (OR = 11.56, 95% CI: 2.45–54.62; p = 0.002) indicated that genetic variants contribute markedly to the likelihood of developing AR. Subgroup analyses further revealed that COX1 and ABCB1 polymorphisms showed the strongest associations, while PTGS1 displayed inconsistent effects. Although high heterogeneity (I2 > 95%) limits precise estimation, these findings reinforce the hypothesis that multiple genetic loci interact to modulate aspirin responsiveness. Collectively, these genes represent distinct pharmacogenetic pathways—drug target modification (COX1/PTGS1), platelet receptor signaling (PEAR1, P2Y1), and drug transport (ABCB1), all potentially converging on altered platelet aggregation thresholds.

This study evaluated the quality of evidence for the outcome indicators using the GRADE system and found it to be low. This was mainly influenced by several factors: Firstly, some of the included studies had a risk of bias, which could lead to an overestimation of the effect size. Secondly, the 95% confidence interval of the combined effect size was wide (4.14 - 91.27), and the number of included studies was relatively small (n = 8), indicating a certain degree of imprecision. Thirdly, substantial heterogeneity was observed across the included studies (I2 consistently > 98%). Although Egger’s test was performed, high heterogeneity persisted; however, it was reduced following subgroup analyses. This indicates that increasing sample size and further stratifying by genotype or assay type may yield more precise and reliable estimates for individualized antiplatelet therapy. A major challenge in synthesizing the current evidence lies in this pronounced heterogeneity, which stems from several factors: (i) variability in platelet-function assays—such as light transmission aggregometry, VerifyNow, thromboelastography, and serum TXB2 measurement—each assessing different biological pathways, (ii) inconsistent diagnostic thresholds used to define AR, and (iii) demographic and clinical differences among study populations. To address this, a random-effects model was employed to account for genuine between-study variability. Although Egger’s regression revealed potential asymmetry in effect sizes, the result did not reach statistical significance (p > 0.05), suggesting minimal but possible publication bias. Collectively, these findings emphasize the urgent need to standardize AR definitions and adopt harmonized platelet-function testing protocols to improve reproducibility, reduce bias, and strengthen cross-study comparability.

COX-1, encoded by the PTGS1 gene, is a central pharmacological target of aspirin and a key determinant of platelet aggregation through its regulation of thromboxane A2 synthesis. Variations in COX-1 and PTGS1 may therefore contribute to AR by altering enzymatic activity or aspirin binding efficiency. In this study, Cao [20] and Li [21] reported that carriers of the CC genotype and T-allele were at increased risk of adverse vascular outcomes and recurrent ischemic events. Similarly, Kirac [22] observed that heterozygous COX-1 variants were more frequent among AR patients, suggesting that COX-1 gene mutations may enhance aspirin non-responsiveness. In contrast, earlier investigations in Caucasian cohorts found no significant association between COX-1 polymorphisms and platelet aggregation or atherothrombotic risk [23-26]. These divergent results may reflect differences in allele frequencies, sample sizes, study power, and diagnostic methodologies across populations. Notably, East Asian populations, including Han Chinese, may exhibit stronger genetic effects due to distinct linkage disequilibrium patterns or environmental modifiers that influence platelet function. The subgroup analysis in the present meta-analysis reinforces the potential role of COX-1 variation in modulating aspirin response.

Evidence regarding PTGS1, which encodes COX-1, remains more controversial. Cai [27] and Zhang [28] identified PTGS1 polymorphisms as independent risk factors for ischemic stroke recurrence in Chinese populations; however, our subgroup analysis did not reach statistical significance, likely due to high heterogeneity and limited sample size. Ikonnikova [29] also demonstrated a higher prevalence of the PTGS1 CC genotype among AR patients, and a meta-analysis reported that carriers of PTGS1 (rs5788) variants exhibited increased atherosclerotic burden [30]. Although other studies have similarly suggested that PTGS1 influences AR [31, 32], inconsistencies persist, probably stemming from variations in ethnicity, sample size, study design, aspirin dosage, and AR definition. Overall, findings from both COX-1 and PTGS1 analyses highlight the central role of this pathway in aspirin pharmacodynamics. Identifying high-risk genotypes may help clinicians predict poor antiplatelet responses and tailor therapy accordingly. Future studies should expand sample sizes, include diverse ethnic groups, and adopt standardized diagnostic criteria for AR to better define the clinical relevance of COX-1 or PTGS1 polymorphisms.

PEAR1 mediates platelet-platelet interactions and downstream activation. The intronic variant rs12041331 (A allele) has been repeatedly implicated in platelet hyper-reactivity [33]. In this review, the PEAR1 polymorphism correlated independently with AR, corroborating prior work by Lewis [34] and Würtz [35], who demonstrated enhanced platelet aggregation among A-allele carriers. However, Li [36] reported no effect in non-Asian populations, emphasizing ethnic-specific variability. Such differences may arise from distinct haplotype structures or environmental modifiers such as diet or smoking. Despite these inconsistencies, PEAR1 remains a promising biomarker for predicting inter-individual variability in aspirin response.

The P2Y1 receptor, a G-protein-coupled receptor responsive to Adenosine Diphosphate (ADP), initiates platelet shape change and aggregation. The P2Y1 C893T polymorphism alters receptor conformation and downstream signalling. The findings of the study and those of Lu [37] demonstrate that carriers of TC/TT genotypes exhibit increased AR risk. Previous studies by Du [38], Grinshtein [39], and Jefferson [40] similarly identified ADP receptor polymorphisms (P2Y1 and P2Y12) as contributors to AR, although others (Bierend [41]) reported neutral results. These divergent outcomes likely reflect small sample sizes and methodological heterogeneity but collectively underscore the role of ADP-mediated pathways in aspirin pharmacodynamics.

The ABCB1 gene encodes P-glycoprotein, an efflux transporter that modulates intestinal drug absorption and systemic bioavailability. The ABCB1 C3435T variant has been associated with altered expression and efflux capacity, potentially influencing aspirin’s plasma concentration [42,14]. In our analysis, the ABCB1 polymorphism demonstrated a significant association with AR (OR = 0.02, 95% CI: 0.00–0.58). Similar trends were observed in Korean (Kim [43]) and Turkish (Yurek [44]) populations, supporting the generalizability of this locus across Asian cohorts. Nevertheless, some studies reported inconsistent results, possibly due to environmental factors and co-medications that affect transporter activity [45]. Given its pharmacokinetic role, ABCB1 may serve as a practical pharmacogenomic target for optimizing aspirin therapy and minimizing treatment failure.

Due to the small sample size (only for Chinese patients with cerebral infarction), this review has limitations. The singularity of the regions where the samples are located and the ethnic singularity may affect the universality of the research results and fail to fully reflect potential differences in responses across populations to aspirin gene polymorphisms. Additionally, this meta-analysis lacks standardization in defining aspirin resistance across studies. The eight included papers employed six distinct platelet-function assays with variable diagnostic thresholds, leading to extreme clinical heterogeneity (I2 ≥ 98%). Although the use of a random-effects model accommodates such variability to some extent, it also reduces the precision of the overall pooled estimate. Consequently, the study findings should be regarded as hypothesis-generating, emphasizing the need for future studies that apply harmonized AR definitions and standardized laboratory methods to improve reproducibility and comparability.

CONCLUSION

This systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrate that genetic polymorphisms, particularly within COX1, PTGS1, PEAR1, P2Y1, and ABCB1, play a potentially important role in modulating AR among Chinese patients with ischemic stroke. Variants in COX1 and ABCB1 showed the most consistent associations with AR, suggesting that both pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic mechanisms contribute to inter-individual variability in aspirin responsiveness. Although other polymorphisms, such as PTGS1, PEAR1, and P2Y1, displayed less consistent effects, they remain biologically plausible contributors to platelet reactivity and warrant further investigation. The marked heterogeneity across studies, arising from differences in AR definitions, platelet function assays, genotyping platforms, and clinical characteristics, limits the precision and generalizability of pooled estimates. Nonetheless, the collective evidence underscores the potential of integrating pharmacogenomic testing into clinical practice to identify patients at higher risk of treatment failure.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: M.H.M.S., R.M.G. and Y.G.: Contributed to the study conception and design; Y.G. and Y.N.: collected the data; Y.G. and Y.N.: Performed the analysis and interpretation of the results; and Y.G., M.H.M.S. and R.M.G.: Prepared the draft manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| COX | = Cyclooxygenase |

| TXA2 | = Thromboxane A2 |

| AR | = Aspirin Resistance |

| AS | = Aspirin Sensitive |

| CI | = Cerebral Infarction |

| NOS | = Newcastle–Ottawa Scale |

| MD | = Mean Difference |

| OR | = Odds Ratio |

| 95% CI | = 95% Confidence Interval |

| PG | = Prostaglandins |

| PEAR1 | = Platelet Endothelial Aggregation Receptor 1 |

| PTGS1 | = Prostaglandin Endoperoxide Synthase 1 |

| GP | = Platelet Membrane Glycoprotein |

| ABCB1 | = ATP-Binding Cassette Sub-family B Member 1 |

| P2Y1 | = Metabolic P2 Receptors 1 |

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

FUNDING

This research was conducted as part of the Jilin Provincial Department of Education project (project no. Jjkh20250825kj).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the staff of the affiliated hospital of Beihua University, China, for their invaluable assistance in data collection, organization, and technical support throughout this study.