All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Medicinal Chemistry and Applications of Incretins and DPP-4 Inhibitors in the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

Abstract

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a major metabolic disorder currently affecting over 200 million people worldwide. Approximately 90% of all diabetic patients suffer from Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). The world's economy coughs out billions of dollars annually to diagnose, treat and manage patients with diabetes. It has been shown that the naturally occurring gut hormones incretins, glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) can preserve the morphology and function of pancreatic beta cell. In addition, GIP and GLP-1 act on insulin receptors to facilitate insulin-receptor binding, resulting in optimal glucose metabolism. This review examines the medicinal chemistry and roles of incretins, specifically, GLP-1 and drugs which can mimic its actions and prevent its enzymatic degradation. The review discussed GLP-1 agonists such as exenatide, liraglutide, taspoglutide and albiglutide. The paper also identified and reviewed a number of inhibitors, which can block dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4), the enzyme responsible for the rapid degradation of GLP-1. These DPP-4 inhibitors include sitagliptin, saxagliptin, vildagliptin and many others which are still in the experimental phase.

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a metabolic disease characterized by hyperglycemia [1]. DM is due to a reduction in the level or effectiveness of insulin. Insulin is produced in the pancreatic islets of Langerhans and induces glucose uptake into liver, muscle and fat cells [2]. Two distinct types of DM have been recognized, Type 1 and Type 2. Type 1 DM, also known previously as insulin-dependent or juvenile onset diabetes, is usually seen in children and young adults, and is caused by the immune-mediated destruction of pancreatic beta cells [3]. Type 2 (T2DM) previously referred to as non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM) is the most common type of diabetes and is characterized by varying severities of insulin resistance [1, 2]. Factors that play a role in the pathogenesis of T2DM include, but not limited to resistance of receptors to the insulin molecule, high glucose release by the liver, reduced insulin-mediated glucose uptake into muscle cells and adipocyte-related cytokines, and less than optimal pancreatic beta cell function. While the current T2DM drugs that enhance insulin release have been therapeutically beneficial, they are associated with several side effects including unpredictable hypoglycemia and body weight gain. Thus, there is a need for more effective drugs, with fewer side effects, to treat T2DM [1-3].

Currently, more than 200 million people worldwide have DM, of which 5-10% are Type 1 while the remaining 90-95% suffer from T2DM [4, 5]. T2DM is caused mainly by a sedentary life style, obesity, hereditary and many other environmental factors [1, 2]. The management of these patients possesses an enormous burden on the healthcare systems worldwide. It is thus of paramount importance, therefore that urgent steps be taken to reduce the cost of managing DM [6].

The pancreatic beta cell mass of a normal person can adapt to different insulin requirements when challenged with different glucose loads. However, the ability of pancreatic beta cell to release optimal and effective insulin may be compromised is diabetes. The inability of pancreatic beta cells to balance insulin resistance is a major problem in patients with impaired glucose tolerance or overt DM. This defect is due to a structural lesion in the insulin molecule or its receptors. It may also be due to the inability of the endocrine pancreas to maintain optimal beta cell mass capable of producing the required amount of effective insulin [5]. This concept has triggered the development of newer therapeutic strategies capable of preserving and/or regenerating a viable pancreatic beta cell mass. Regeneration, undoubtedly, is regulated by a constant interplay of beta cell growth (replication from mature beta cells and de novo formation from precursor cells in pancreatic tissue) and beta cell death (mainly by apoptosis) [8]. Disruption of this interplay may lead to rapid and large changes in the viability of pancreatic beta cell mass. A new class of bioactive agents called incretins, originally developed to counter postprandial hyperglycaemia, have been observed to be capable of enhancing beta cell survival, thus contributing to the long-term, optimal regulation of insulin secretion. The development of drugs that regulate pancreatic beta cell mass will be a strong tool in the management of patients with T2DM [9].

Long term T2DM put a lot of stress on pancreatic beta cells. The impact of high work load and hyperglycaemia-induced oxidative stress lead, eventually, to pancreatic beta cell death. Some T2DM patient may thus convert to T1DM patients in severe cases. Any bioactive agent, including incretins and DPP-4 inhibitors, that is capable of reducing hyperglycemia directly or indirectly can prevent pancreatic beta cell loss and facilitate its regeneration.

THE THERAPEUTIC ROLE OF INCRETINS IN DIABETES MELLITUS

It has long been shown that hormones of the gastrointestinal system can modulate the secretory activities of the islets of Langerhans. Studies have shown that insulin release is much greater when glucose is ingested by mouth compared to when it is administered intravenously [10]. These bioactive agents mediating the greater insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells in response to oral glucose were referred to as incretins [11, 12].

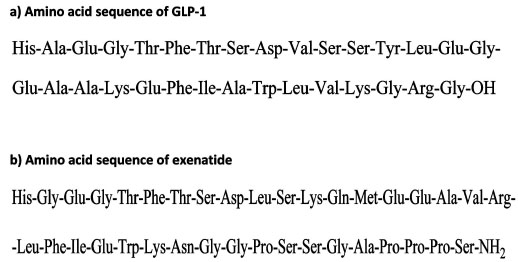

The first set of biologically active incretins to be identified was the gut-derived hormone glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) [13-15]. GIP is also known as gastric inhibitory polypeptide. Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) as shown in Fig. (1) was recognized to have a potent insulinotropic activity, and collectively, GIP and GLP-1 have been shown to account for as much as 50% of the insulin released immediately after meal ingestion [15]. GIP and GLP-1 exert their physiological effects via the activation of their respective, almost ubiquitous trans-membrane G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCR), which amount to about seven in number. These GLP specific GPCRs are found on a variety of tissues in addition to pancreatic beta cells, indicating that incretins have other biological roles beyond that involving the release of insulin into the blood stream [15, 16]. GLP-1 also inhibits emptying of food from the stomach; thus increases satiety in general and, therefore, decreases food intake. It is also believed that GLP-1 influences learning and memory and has been implicated in the regulation of several cardiovascular functions [17-20]. A number of extrapancreatic effects, including the promotion of lipolysis in adipocytes and maintenance of bone mass have also been attributed to GIP by many investigators [16, 21, 22]. Although these two incretins (GIP, GLP-1) promote beta cell survival with a concomitant increase in plasma insulin level, they have different effects on how glucagon is secreted. GIP stimulates glucagon release, while GLP-1 inhibits it [15, 23].

Amino acid sequence of GLP-1 (a) and exenatide (b).

GIP and GLP-1 are quickly deactivated by dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) [24]. DPP-4, found in many types of tissues, can cleave the active peptide at position 2 alanine (N-terminal) resulting in an inactive compound [25]. Previous reports have shown that DPP-4 is also found in the endothelium of capillaries that drain the intestinal mucosa where GLP-1-secreting cells are situated [25, 26] indicating that most of the GLP-1 is inactivated almost immediately, following secretion. This immediate degradation of GLP-1 and GIP contributes to very short half-lives of less than 2 min and 5–7 min, respectively [24, 25, 27, 28]. This short half-life limits the therapeutic potential of incretins. To overcome this problem, modifications of the amino acids at the N-terminus of GLP-1 or GIP were done. The disadvantage of this phenomenon is that these modifications may result in insensitivity to the DPP-4 molecule, leading to unpredictable levels of biological effects [29].

SELECTED INCRETIN AGONISTS

Exenatide

Exenatide is a synthetic form of exendin-4, a naturally occurring peptide consisting of 39-amino acids [24, 30] (Fig.1). It was originally isolated from the salivary fluid of the lizard Heloderma suspectum (gila monster). It is a partial structural analogue of human GLP-1 and shares 53% amino acid sequence similarity with human GLP-1. It functions as an incretin-mimetic polypeptide, which binds to and stimulates GLP-1 receptor located on plasma membranes. GLP-1 receptor belongs to the class of ubiquitous, transmembrane receptors known as GPCR (G-protein couple receptors). In contrast to GLP-1 peptide, which contains the amino acid alanine at position 2, exenatide instead has glycine at position 2, making it unrecognisable by DPP-4. This modification allows exenatide to have much longer plasma half-life compared to GLP-1 [24, 31].

Exenatide has been shown to be able to help maintain beta cell mass and function by increasing the expression of beta-cell genes which promote islet-cell proliferation and neogenesis, and inhibit apoptosis in pancreatic islet cells [32-36]. Exenatide has a short-term effect on pancreatic beta-cell responsiveness to glucose, leading to insulin release especially when the body is faced with acute hyperglycemia. Insulin secretion is thus reduced as blood glucose levels gradually decrease [31].

Liraglutide (a Fatty Acid Derivative of GLP-1)

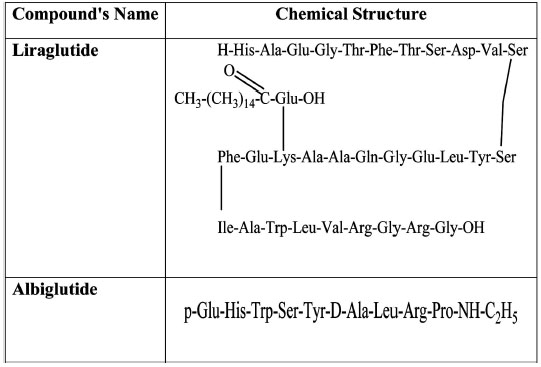

Liraglutide is an analogue and fatty acid derivative of GLP-1. Its 16-carbon fatty acid chain is linked to Lys as shown in (Fig. 2). This association masks the cleavage point of liraglutide making it resistant to DPP-4 degradation [29], in a similar way as exenatide. Liraglutide, at therapeutic concentrations, lowers fasting and post-prandial plasma glucose in patients suffering from T2DM [37] and delays the outflow of food from the stomach [38]. It also produces a gradual increase in insulin release depending on the glucose load, via improvements in pancreatic beta cell viability (increases in cell mass coupled with inhibition of apoptosis). [39-41]. Like GLP-1, liraglutide suppresses glucagon in a glucose-dependent manner, immediately after a meal is taken [38].

Chemical structure of Liraglutide and Albiglutide.

Other Incretin Analogues and Agonists

The introduction of a long acting exenatide (manufactured by Eli Lilly), capable of reducing HbA1c, fasting plasma glucose and body weight is currently undergoing clinical trials [42-44]. These promising results have led to the development of taspoglutide, a long-acting, once-a-week analogue of GLP-1 by Roche and its European Pharmaceutical Company, Ipsen. Initial studies have shown that this long-acting GLP-1 analogue induces a lower HbA1c and causes significant body weight loss [45]. Albiglutide (Glasgow SmithKline) is an albumin-fusion GLP-1 agonist [46], with a plasma half-life of 7 days and a T-max of 3–4 days [47, 48], can maintain therapeutic levels for a much longer time in the body. Albiglutide treatment causes reductions in 24-h weighted mean glucose and postprandial concentrations with a relatively low risk of the patient being hypoglycemic [47]. It also stimulates GLP-1 receptor–dependent signalling pathways resulting in insulin release leading to reduction in blood glucose level [49]. (Fig. 2).

Use of Recombinant Technology to Modify GLP-1 Action

The administration of rAd-GLP-1 (recombinant adenoviral vector expressing GLP-1) to experimental diabetic mice resulted in remission of DM within a period of 10 days. In addition, normoglycaemia persisted until the end of the experiment [50]. Gene transfer of the plasmid coding for the GLP-1/Fc peptide in db/db mice has shown that animals hosting the plasmid displayed a normalized glucose tolerance curve compared to control [51]. It does appear, therefore, that gene therapy can facilitate overexpression of GLP-1 related peptides and could therefore have a potential therapeutic significance in the treatment of diabetes mellitus in the future.

The Dipeptidyl-Peptidase 4 (DPP-4) as a Target Enzyme in the Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus

The half life of a functional GLP-1 molecule is less than 2 min and that of GIP is approximately 7 min [52]. Thus indicating that without changing their molecular structure, these incretins cannot be used therapeutically because of rapid clearance from body systems. This complete and rapid clearance of incretin hormones is via DPP-4. Thus, inhibition of DPP-4 to prevent the fast decay of incretins appears to be a promising therapeutic goal in the treatment of diabetes [53].

DPP-4 is a large, 766 amino acid membrane-associated, serine-type protease enzyme. For DPP-4 to be effective, a dipeptide must cleave off from the N-terminal [54]. The enzyme is widely detected in numerous tissues such as kidney, liver, intestine, spleen, lymphocytic organs, placenta, adrenal glands, and vascular endothelium. DPP-4 inhibitors exert their hypoglycaemic effect indirectly by improving the longevity, plasma concentration and action of incretins [55].

DPP-4 inhibitors are orally active, small molecular weight drugs that can inhibit more than 90% of plasma DPP-4 activity for over 24 h period [56]. These agents increase active incretin levels by preventing their rapid degradation. Thus, DPP-4 inhibitors are dependent on endogenous incretin secretion and could thus be effectively used early in T2DM, when pancreatic beta cell store of insulin is not completely exhausted [57].

A major mechanism underlying the anti-diabetic effect of DPP-4 inhibitors is increased concentrations of biologically active GLP-1 and GIP, as has been shown after ingestion of a meal [58]. This DPP-4 inhibitor induced increase in the concentration of GLP and GIP persists during an entire 24 h period [59]. DPP-4 inhibitor administration also induces improved pancreatic beta cell activity, as shown by improved insulin release [59, 60], and reduced inactive insulin-to-active insulin ratio [61, 62]. DPP-4 inhibition also suppresses glucagon release [58, 59], which corresponds to reduction in hepatic glucose production. This is particularly important because a worsening diabetes is associated with an increase in the level of glucagon. Insulin sensitivity is improved resulting in reduced plasma blood glucose levels after DPP-4 inhibition [63-65].

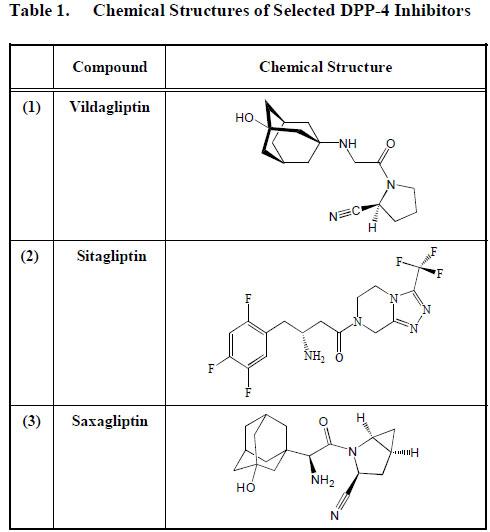

Several DPP-4 inhibitors have been produced [66, 67], and they include vildagliptin (1) (LAF237) marketed as Galvus, by Novartis; sitagliptin (2) (MK-0431) sold as Januvia by Merck and saxagliptin (3) (BMS-477118, a product of Bristol-Myers Squibb, that competitively and reversibly inhibit the enzyme, DPP-4 [68-70]. These DPP-4 inhibitors are rapidly absorbed when given orally and the Cmax is observed within 1-2 h of administration. Bioavailability is said to be more than 80% after oral dosage.

Vildagliptin (1) is hydrolyzed to an inactive compound excreted via the kidney into urine. However, approximately 20% of vildagliptin (1) is disposed from our body unchanged. In contrast, sitagliptin (2) is primarily excreted as is by the kidney and, therefore, renal insufficiency may increase the circulating level of sitagliptin (2) [71] leading to abnormal plasma levels of the drug. An overdose of sitagliptin (2) may possibly lead to hypoglycaemia. The metabolism of saxagliptin (3) occurs mainly in the liver. The active compound and unconverted saxagliptin (3) and other metabolites are however, released via the kidney into urine. Hepatic insufficiency does not seem, therefore, to alter the pharmacokinetics of these compounds. Drug-drug interaction does not seem to be an issue with patients taking DPP-4 inhibitors [71]. (Table 1).

Chemical Structures of Selected DPP-4 Inhibitors

|

Sitagliptin

Sitagliptin (2) (MK-0431) is an oral preparation of a DPP-4 inhibitor [72]. It has been approved by the FDA as a single therapy for the treatment of diabetes but can be added to metformin or glitazone, when metformin plus diet regimen is not producing the required result [73, 74]. In Europe, a monotherapy with sitagliptin (2) is given either primarily for patients with a new onset of diabetes mellitus or because of ineffectiveness of other oral hypoglycaemic agents. Several reports have suggested that sitagliptin (2) can be added to either metformin, or glitazone, a sulfonylurea, or in a triple combination with both metformin and a sulfonylurea, but not with a glinide [61, 75, 76]. A combination of sitagliptin (2) with metformin in particular has been reported to be beneficial for an optimal pancreatic beta cell function [77, 78].

Sitagliptin (2) when given alone can induce large inhibition in DPP-4 activity of up to 96% at 2 h, and 80% at 24 h after administration [79]. A single oral course of sitagliptin (2) was reported to increase GLP-1 response to oral glucose tolerance test significantly, resulting in a large decrease in blood glucose level [79].

Administration of sitagliptin to streptozocin-induced diabetic rats, fed on high-fat diet caused large and significant increases in the number of pancreatic beta cells in the islets of Langerhans, resulting in improved beta cell mass and beta-cell-to-alpha-cell ratio. Sitagliptin (2) also reduced the plasma level of HbA1c, triglycerides and free fatty acids in rodent models of diabetes [80]. In patients suffering from T2DM, the administration of sitagliptin (2) increases the plasma levels of insulin and C-peptide with a concomitant reduction in the plasma level of glucagon [79], resulting in a well balanced glycemic control (Table1).

Vildagliptin

Vildagliptin (1) (LAF237) marketed as Galvus® is the second DPP-4 inhibitor to be approved, in 2008, in the Europe Union for the management of diabetes mellitus. The molecular structures and pharmacokinetics of sitagliptin (2) and vildagliptin (1) are different. Sitagliptin (2) is a competitive antagonist of DPP-4 while vildagliptin (1), as well as saxagliptin (3) are substrates for DPP-4, thereby inhibiting the target molecule. Vildagliptin (1) has a high affinity for DPP-4 [62, 81, 82]. This strong affinity enables vildaliptin (1) to induce large reductions in the plasma HbA1c level of patients with T2DM [83]. In addition, vildagliptin (1) increases fasting and postprandial GLP-1 level, and induces pancreatic beta cell sensitivity to glucose and insulin. It also has the ability to significantly lower postprandial lipaemia. In contrast to many other DPP-4 inhibitors, vildagliptin (1) does not slow the outward flow of food from the stomach. These therapeutic effects of vildagliptin (1) described above may help to improve glucose tolerance and achieve normoglycemia [84-86]. Other study showed that vildagliptin (1) can significantly increase insulin release [87] with a simultaneous reduction in glucagon levels especially in the post-meal period [88, 89].

Vildagliptin (1) causes a reduction in glucagon/insulin ratio and a lower endogenous glucose production during both the postprandial and post-absorptive phases [87]. Clinical trials have shown that vildagliptin (1) induces significant improvements in glycemic control in T2MD patients as demonstrated by large reductions in the level of HbA1c when used alone or in combination with other hypoglycaemic agents such as metformin. Although vildagliptin (1) improves pancreatic beta cell function in patients with T2DM it does not contribute to body weight gain [60]. The plasma concentration of proinsulin, a marker of abnormal beta cell function, is significantly reduced in patients treated with vildagliptin (1) [62]. Vildagliptin (1) can reduce lipolysis as well as postprandial hypertriglyceridemia [89] probably because of vildagliptin-induced higher plasma concentration of incretin, which has been reported to reduce intestinal absorption of triglyceride in animal studies [90]. (Table1).

Saxagliptin

Saxagliptin (3) is a relatively new selective and reversible DPP-4 inhibitor, developed by Bristol-Myers Squibb and AstraZeneca for the treatment of diabetes mellitus. The phase 3 clinical trial of saxagliptin (3) has recently been completed [91]. Saxagliptin was approved by the FDA in July 31, 2009 and marketed under the tradename of Onglyza®. It is a highly potent DPP-4 inhibitor, about 10 times more potent than either vildagliptin (1) or sitagliptin (2) [92]. The first clinical study shows that saxagliptin (3) can reduce the signs and symptoms of diabetes mellitus. It has the ability to reduce HbA1c level when given, once-daily, to drug-naive patients [93, 94]. Saxagliptin (3) also induced large and significant reductions in fasting and postprandial blood glucose levels [93, 95].

Some studies have examined the efficacy of saxagliptin (3) and other drugs in inadequately controlled patients with T2DM in terms of the degree of reductions in HbA1c. The administration of oral saxagliptin (3) at 2.5-10 mg, once-daily, in combination with metformin provided significant reductions in HbA1c level when compared to placebo. Saxagliptin (3) caused large reductions in blood glucose levels compared to placebo [96]. It has been reported that patients tolerate saxagliptin (3) well, as it does not cause significant hypoglycemia. The effect of saxagliptin (3) on body weight gain has not been widely assessed, but the limited data available in the literature suggest that it has little or no impact on body weight [91] (Table1).

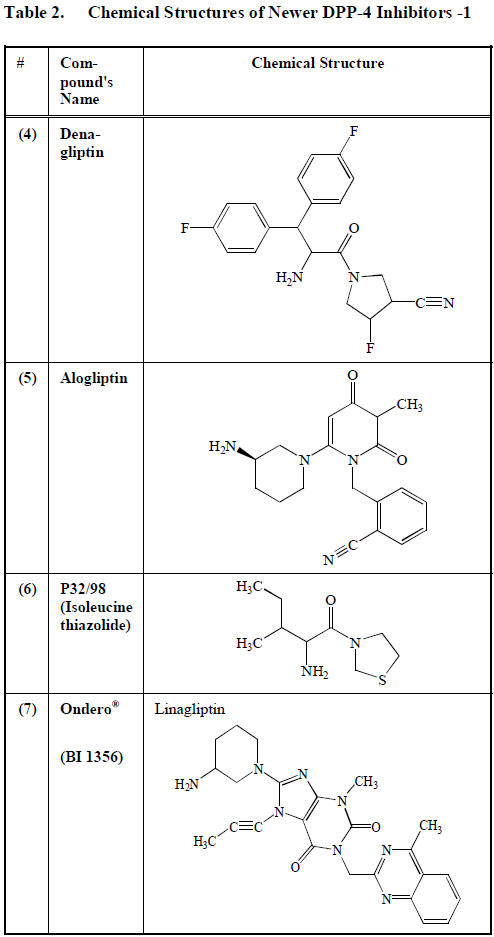

Newer DPP-4 Inhibitors

Denagliptin (4), produced by Glaxo Smith Kline, showed significant differences in its pharmacokinetics, side-effects and clinical activity when compared to the currently available DPP-4 inhibitors such as vildagliptin and saxagliptin. This may be due to the extra fluoride molecules that denagliptin (4) has. The clinical effects attributed to denagliptin (4) have not been thoroughly documented [97]. Denagliptin is still very much in the experimental phase and awaits approval for use in clinical practice (Table2).

Chemical Structures of Newer DPP-4 Inhibitors -1

|

Alogliptin (5) (SYR-322) developed by Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, Japan, is a quinazolinone-denominated DPP-4 antagonist. It has been reported that between 45% and 88% of the total alogliptin ingested orally is available for biological action [98]. The few studies performed on the effect of alogliptin in diabetics have shown its ability to normalize glycemic levels [99]. (Table2).

P32/98 (6) also called Isoleucine thiazolidide has been reported to increase pancreatic beta cell mass in animal models of diabetes [100] (Table2). However, further reports are still needed to investigate its role in the management of diabetes mellitus and any possible side effects.

Linagliptin (BI 1356) (7) developed by Boehringer-Ingelheim, was given the trade name of Tradjenta. BI 1356 (7) is a xanthine derivative with a strong capacity to dissociate DPP-4 at a very low velocity. Initial investigations have shown that BI 1356 (7) attaches to its main target molecule at low plasma concentrations, making it an ideal drug. The in vivo duration of action of BI 1356 (7) is more prolonged when compared to other DPP-4 inhibitors, making it possible to be administered as a once-a-day anti-diabetic drug [101]. A once-a-day regimen will improve compliance in patients with a busy schedule. Although BI 1356 (7) increases basal GLP-1 level, it does not increase plasma insulin concentration in rats 24 h after its administration [102]. BI 1356 (7) has been shown to be able to produce more than 80% DPP-4 inhibition at therapeutic dosage [102] (Table2).

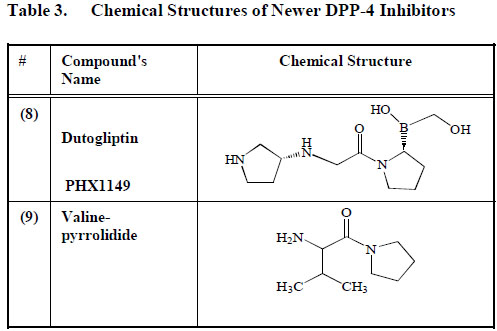

Dutogliptin (PHX1149) (8), manufactured by Phenomix Corporation, is an aqueous DPP-4 inhibitor. It is excreted unconverted in urine and has a long half-life of between 10 to 13 h [103] Table 3. SK-0405 an even newer compound can inhibit DPP-4 for an even longer period, when compared to vildagliptin (1) [104]. Many other DPP-4 inhibitors, including P93/01, NVP-DPP728, 815541A, GSK23A and valine-pyrrolidide (9) are still in the experimental phase, and little is known therefore about their mechanism of action or possible side effects (Table3).

Chemical Structures of Newer DPP-4 Inhibitors

|

Neutral endopeptidase (NEP), a membrane-bound metallo-endopeptidase, which can degrade amyloid beta has also been shown to be capable of degrading small peptides, including GLP-1 [105]. In fact it has been shown that NEP-24.11 can degrade as much as 50% of GLP-1 in circulation. Therefore, the inhibition of both DPP-4 and NEP-24.11 would be superior to the inhibition of DPP-4 alone in the maintenance of optimal therapeutic level of GLP-1 [106].

Advantages, Disadvantages and Limitations of Incretins and DPP-4 Inhibitors

Like any other group of drug, incretins and DPP-4 inhibitors have their pros and cons. The positive side of incretins is their ability to stimulate secretion in a glucose-dependent manner thereby reducing the possibility of sudden hypoglycaemia. Satiety and weight loss can also be achieved during treatment with incretins [107-109]. The chance of compliance is high in patients taking incretin/incretin mimetics because they can be dispensed once a day or even once in week. The down side of increting and its analogue is that they can only be given by injection [110], which comes along with fear of injecting oneself and infection at sites of administration. In addition, some classes of incretin analogue (liraglutide) have been shown to cause thyroid C-cell neoplasm, at least in rodent models (Tables 4 and 5a-b).

Advantages, Disadvantages and Limitations of GLP-1, Agonists and its Analogues

| Advantages | Disadvantages | Limitations | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GLP-1 | Can only be given subcutaneously [110] | ||

| Liraglutide (a GLP-1 analogue) |

|

|

|

| Albiglutide (a GLP-1 analogue) |

|

Can only be given subcutaneously [110] |

Advantages, Disadvantages and Limitations of Newer DPP-4 Inhibitors

| Advantages | Disadvantages | Limitations | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vildagliptin |

|

|

|

| Sitagliptin |

|

|

|

| Saxagliptin |

|

Advantages, Disadvantages and Limitations of Newer DPP-4 Inhibitors

| Advantages | Disadvantages | Limitations | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Denagliptin |

|

|

|

| Alogliptin |

|

|

|

| P32/98 (Isoleucyl thiazolidide) |

|

|

|

| Linagliptin (BI 1356) |

|

|

|

| Dutogliptin PHX1149 |

|

|

|

| Valine-pyrrolidide | Inhibits DPP-8 as well |

|

CONCLUSION

The pathology and course of T2DM involves a progressive malfunction of pancreatic beta cell due in part to insufficient mass. The incretins including GIP and GLP-1 play a role in the regulation of glucose metabolism via meal-stimulated insulin release. Even though diabetic patients may display a lower sensitivity to GIP, their reactions to GLP-1 are largely conserved. Therefore, the maintenance of an optimal GLP-1 level would be a logical strategy for the treatment of patients with T2DM. Optimal GLP-1 level can be achieved by the use of long-acting GLP-1 receptor agonists or alternatively by DPP-4 inhibitors in order to prevent degradation of incretins. GLP-1 can reduce postprandial hyperglycemia, delay the outflow of food from the stomach, reduce appetite, body weight and preserve pancreatic beta cell mass.

Since DPP are ubiquitous and are involved in the suppression of tumour cells, subclasses of DPP-4 inhibitors that are more selective for enzymes that degrade incretins that will cause less adverse effect are the future drugs in this class.