All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Design, Synthesis, and In Vitro Preliminary Cytotoxicity Evaluation of New Anthraquinone-2-Carboxylic Acid Derivatives

Abstract

Introduction

DNA intercalators are among the most clinically effective anticancer drugs, targeting topoisomerase, a crucial enzyme that regulates DNA topology during essential cellular functions. Several topoisomerase inhibitors are widely used in clinical oncology. However, their application is often limited due to severe side effects and dose-dependent toxicity, necessitating continuous efforts to develop innovative and efficient therapeutic approaches. This study aimed to perform a virtual evaluation, synthesize, and examine the in vitro cytotoxic activity of six newly designed compounds. These compounds were derived from the hybridization of an anthraquinone scaffold with N-acyl hydrazone and N-acyl sulfonyl hydrazide derivatives, using amino acids, specifically proline and glycine, as linkers.

Methods

The plausible inhibitory effect of the designed compounds against the topoisomerase enzyme was evaluated in silico using Maestro software from Schrödinger. Molecular dynamics simulations were conducted to assess compound stability and interaction behavior. Pharmacokinetic properties (ADME) were evaluated to determine compliance with drug-likeness standards. The compounds were successfully synthesized and purified using conventional synthetic techniques. The synthesized intermediates and final products were characterized by melting points, TLC, FT-IR spectroscopy, 1H NMR, and 13C NMR studies. In vitro cytotoxic activity was assessed using the MTT assay against the human colonic cancer (HCT-116) cell line.

Results

Most designed compounds exhibited higher docking scores than the reference compound, doxorubicin. Compound 3a demonstrated good stability and favorable interaction behavior in molecular dynamics simulations. The MTT assay revealed significant concentration-dependent inhibition of HCT-116 cell growth, with IC50 values of 15.85 µM and 22.46 µM for compounds 3a and 4c, respectively.

Discussion

The results revealed appreciable cell growth inhibition and topoisomerase targeting, indicating that anthraquinone hybrids may serve as lead structures with improved therapeutic profiles, paving the way for more effective and less toxic anticancer agents.

Conclusion

The newly designed anthraquinone hybrids exhibited strong topoisomerase inhibitory activity and potent cytotoxic effects, highlighting their promise for further development as anticancer agents.

1. INTRODUCTION

Cancer is ranked as the second leading cause of death globally [1], poses a significant obstacle to human health and life expectancy. Despite significant advancements in cancer treatment, including gene and immunotherapy, chemotherapy remains a cornerstone in oncological care, either as a standalone approach or in combination with other modalities such as surgery and radiotherapy. The effectiveness of conventional chemotherapeutic agents is limited by high toxicity and resistance from cancer cells, which underscores the urgent need for developing drugs that are more potent and selective for cancer cells [2].

Anthraquinone derivatives, such as doxorubicin and daunorubicin, are among the most effective chemotherapeutic agents, exerting cytotoxic effects by interfering with essential cellular processes [3]. These drugs target topoisomerases, enzymes that regulate DNA topology to maintain key cellular processes such as replication, recombination, and chromosome condensation [4]. Topoisomerases are classified into two types based on their mechanism: Type I cuts one DNA strand to relieve supercoiling, while Type II cuts both DNA strands and is divided into Topo IIα and Topo IIβ subtypes [5, 6]. The anthraquinone ring system, a crucial structural component of anthracyclines, enables the medication to intercalate into DNA and disrupt the helical structure. These dual mechanisms, DNA intercalation via the anthraquinone ring and topoisomerase II inhibition, make anthracyclines highly effective against many cancers. However, their clinical use is limited by dose-dependent cardiotoxicity and drug resistance [7, 8].

The antitumor activity of anthraquinone derivatives is highly influenced by the incorporation of various substituents into their aromatic planar structure. Side groups of anthraquinone derivatives stabilize electrostatic interactions with the phosphate backbone of the polynucleotide chain, ensuring effective inhibition of topoisomerase II [9].

Tumor cells exhibit a significantly higher demand for amino acids, which are essential for protein synthesis, compared to normal cells. Thus, the study explores the conjugation of amino acids proline and glycine with anthraquinone derivatives to improve their solubility and selective accumulation in tumor tissues, highlighting their potential in cancer therapy [10]. Amino acid–based structures represent a promising alternative to conventional amino-sugars in anthraquinone derivatives, offering a potential strategy to overcome efflux-mediated drug resistance [11].

Schiff base–modified anthraquinone derivatives show pivotal anticancer potential [12, 13], particularly due to their ability to inhibit topoisomerase II [9]. Owing to their structural features as pharmacophores and the diverse substituents attached to them, N-acyl hydrazones exhibit remarkable versatility in both molecular design and biological activity [14]. Thus, introducing tautomerizable groups, such as N-acyl hydrazone, enhances interactions with DNA and may enable selective recognition of oncogenic targets. Collectively, these features contribute to improved cytotoxicity and offer a strategy to overcome drug resistance mechanisms [15].

Incorporating polar sulfonamide groups into anthraquinone derivatives has demonstrated its ability to boost their anticancer efficacy while minimizing toxicity [16]. This is attributed largely to the fact that the sulfonamide moiety enhances DNA binding affinity, enabling stronger interactions with the phosphate backbone and promoting more efficient intercalation [17]. Additionally, sulfonamide is frequently used as a bioisostere for the carboxylic acid group in medicinal chemistry due to its favorable physicochemical properties [18]. As a result, this alteration in structure also improves cellular uptake and selectivity, positioning these conjugates as highly promising options for designing targeted cancer candidates [19]. Building on this strategy, researchers have found that sulfonyl hydrazide groups have also emerged as potent pharmacophores in anticancer drug design by enhancing cytotoxic activity. In these contexts, sulfonyl hydrazides function as nucleophiles, electrophiles, and radical precursors in many tandem reactions. Reflecting this progress, over the past decade, numerous reliable drugs have been developed, encompassing sulfonyl hydrazides [20, 21].

Based on earlier findings, the primary objective of this study was to design, perform docking studies, synthesize, and conduct biological examinations on a new series of anthraquinone derivatives. The focus was on the main pharmacophoric features of DNA intercalators and the anthraquinone core structure of doxorubicin.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Materials and Equipment

Starting materials and reagents were procured from multiple commercial suppliers (Macklin, TCI, Thomas Baker, Sigma Aldrich, LOBA Chemie). All chemicals used were of analytical grade and utilized directly, without any additional purification steps. The progress of reactions and the purity of compounds were monitored and verified through thin-layer chromatography (TLC) plates from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany, silica gel 60 F254) and exposed to UV-254nm light. The melting points were measured using a Stuart SMP30 melting point apparatus, employing the one-end sealed capillary tube method. Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy was performed using the Shimadzu IR Affinity-1 spectrometer manufactured by Shimadzu (Kyoto, Japan). The 1H NMR and 13C NMR analyses were conducted at Hamdi Mango Center for Scientific Research (HMCSR)/ The University of Jordan, using a Bruker 500 MHz (BioSpin GmbH, Rheinstetten, Germany) spectrometer with deuterated dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO-d6) as solvent and the chemical shifts (δ) expressed in parts per million.

2.2. Molecular Docking

Molecular docking is a crucial method for identifying potential binding sites and interactions between designed compounds and proteins. Glide software from Schrodinger’s modeling suite was used to conduct the docking investigation. The human Topoisomerase II beta protein structure (4G0V) was downloaded from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) [22], and doxorubicin was used as a reference ligand [9, 23]. The ChemDraw software from the PerkinElmer suite was used to draw the chemical structures of compounds, which were then optimized by LigPrep in the Maestro suite [24]. Standard precision (SP) docking was carried out using grid-based ligand docking with the Glide program for all designed compounds on the mentioned protein. The best docking poses of compounds were ranked according to their docking score and interactions within the Maestro interface (Schrodinger, New York, version 2025.4).

2.3. Molecular Dynamic Simulation

We performed molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of compound 3a to evaluate the durability and compatibility of ligand intercalation with the DNA of the target protein 4G0V. These simulations were carried out using the Desmond software integrated within the Maestro interface (Schrödinger Release, 2025.4). The simulation system was prepared using the System Builder tool, employing the simple point charge (SPC) water model and enclosed in an orthorhombic periodic box measuring 10 Å on each side from the outermost edge of the protein. The OPLS4 force field was applied for system parameterization. To maintain a neutral pH, sodium (Na+) and chloride (Cl−) ions were added for charge balancing. Simulations were performed under NPT ensemble conditions at 300 K and 1 bar pressure, with a total duration of 200 nanoseconds [25, 26].

2.4. In Silico ADME Study

In order to assess the drug-likeness of the developed compounds, the ligands were subjected to structure-based ADME property prediction using the QikProp tool within Maestro software and rapid mode, with the option to “Identify the 5 most similar drug molecules” activated [27].

2.5. Chemical Synthesis

2.5.1. Synthesis of Ethyl (9, 10-dioxo-9, 10-dihydroanthracene-2 carbonyl)glycinate (1a) [28]

Glycine ethyl ester HCl (0.618 g, 4.43 mmol, 1.2 equiv.) was suspended in 15 mL of dry dichloromethane (DCM) in a 250 mL round-bottom flask and placed in an ice bath. Triethylamine (1.23 mL, 8.86 mmol, 2 equiv.) was added dropwise over 2 min, and the reaction mixture was maintained at 0°C for 30 min with constant stirring. Anthraquinone-2 carbonyl chloride 1 (1 g, 3.69 mmol, 1 equiv.) was dissolved in 30 mL of dry DCM, which was then slowly added to the reaction mixture and stirred at 0°C for 1 h before being refluxed at 45–55°C for 3 h. TLC monitored the completeness of the reaction. After evaporation of the solvent, the residual precipitate was dissolved in 15 mL of ethyl acetate, transferred to a separatory funnel, and washed several times with distilled water, 5% NaHCO3, and 2% HCl. The organic layer was collected and dried. Yellow shiny powder. Yield: 92%; m.p. 186-187°C; FT-IR (cm-1, str.vib.): 3294 (2° amide N-H), 3070 (aromatic C-H), 2989, 2939 (aliphatic C-H), 1743 (ester C=O), 1674 (ketone C=O), 1643 (2° amide C=O), 1593-1450 (aromatic C=C). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.43 (t, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H, 2° amide N-H), 8.65 (s, 1H), 8.33 (d, 1H), 8.28 (d, 1H), 8.21 (m, 2H), 7.93 (m, 2H), 4.15 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H, ethyl CH2), 4.07 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, 2H, 2° amide CH2), 1.22 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H, ethyl CH3). 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 182.23, 170.09, 165.46, 138.76, 134.96, 133.33, 133.20, 127.50, 127.15, 125.95, 61.07, 41.92, 14.55.

2.5.2. Synthesis of N-(2-hydrazineyl-2-oxoethyl)-9, 10-dioxo-9, 10-dihydroanthracene-2-carboxamide (2a) [29]

In a round-bottom flask, compound 1a (0.5 g, 1.48 mmol, 1 equiv.) was dissolved in 20 mL of n-butanol. Hydrazine hydrate 100% (0.74 g, 14.8 mmol, 10 equiv.) was then slowly added, and the reaction mixture was refluxed at 110°C for 2 h until a precipitate formed. TLC monitored the completeness of the reaction. The mixture was poured into a separatory funnel and extracted with distilled water. The organic layer was collected, filtered, and rinsed with ether, followed by hot ethanol. White fluffy powder. Yield: 91.5%; m.p. 245–247°C; FT-IR (cm-1, str.vib.): 3325 (1° amine N-H), 3244 (2° amides and sym 1° amine N-H), 3039 (aromatic C-H), 2931 (aliphatic C-H), 1670 (ketone C=O), 1643 (2° amides C=O), 1585-1477 (aromatic carbons C=C). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.23 (s, 1H, hydrazide N-H), 9.20 (t, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H, 2° amide N-H), 8.64 (s, 1H), 8.32 (d, J = 8.1 Hz,1H), 8.24 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.18 (m, J =3.4 Hz, 2H), 7.91 (m, J =3.6 Hz, 2H), 4.26 (s, 2H, hydrazide NH2), 3.90 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 2H, 2° amide CH2). 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 182.60, 168.48, 165.49, 139.42, 135.14, 135.05, 133.53, 133.49, 133.44, 127.46, 127.31, 127.27, 126.25, 42.07.

2.5.3. General Procedure for the Synthesis of Glycine Schiff Bases

Compound 2a (0.16 g, 0.5 mmol, 1 equiv.) was ground separately with (0.74 mmol, 1.5 equiv.) (0.108 g 4-chlorobenzaldehyde and 0.11 g 4-dimethylaminobenzaldehyde). The mixtures were placed in a 100 mL round-bottom flask and dissolved in 20 mL of absolute methanol. Four drops of glacial acetic acid were added to each, and then the mixtures were refluxed at 65–70°C for 3 h to obtain a precipitate of product 3a and 3b, respectively. The precipitates were filtered and purified by washing with hot methanol [30].

2.5.3.1. (E)-N-(2-(2-(4-chlorobenzylidene) hydrazineyl)-2-oxoethyl)-9, 10-dioxo-9, 10-dihydroanthracene-2-carboxamide (3a)

Yellow fluffy powder. Yield: 90%; m.p. 287–290°C; FT-IR (cm-1, str.vib.): 3367 (2° amide N-H), 3251 (N-acyl hydrazone N-H), 3059 (aromatic C-H), 2950 (aliphatic C-H), 1689 (ketone C=O), 1666 (2° amide and N-acyl hydrazone C=O), 1612 (N-acyl hydrazone C=N), 1585-1485 (aromatic carbons C=C). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.63 (s, 1H, N-acyl hydrazone N-H), 9.23 (t, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H, 2° amide N-H), 8.70 (s, 1H), 8.37 (d, 1H), 8.32 (d, 1H), 8.23 (m, 2H), 8.01 (s, 1H, imine N=CH), 7.95 (m, 2H), 7.75-7.49 (m, J = 8.2 Hz, 4H), 4.49, 4.06 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, 2H, 2° amide CH2). 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 182.63, 170.53, 165.63, 142.72, 139.37, 135.17, 133.60, 133.34, 129.37, 128.95, 127.65, 127.35, 126.06, 41.46.

2.5.3.2. (E)-N-(2-(2-(4-(dimethylamino) benzylidene) hydrazineyl)-2-oxoethyl)-9, 10-dioxo-9, 10-dihydroanthracene-2-carboxamide (3b)

Purple fluffy powder. Yield: 90%; m.p. 271–274°C; FT-IR (cm-1, str.vib.): 3360 (2° amide N-H), 3240 (N-acyl hydrazone N-H), 3066 (aromatic C-H), 2947-2812 (aliphatic C-H), 1678 (ketone C=O), 1651 (2° amide and N-acyl hydrazone C=O), 1604 (N-acyl hydrazone C=N), 1589-1485 (aromatic C=C). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.27 (s, 1H, N-acyl hydrazone N-H), 9.36, 9.19 (s, 1H, 2° amide N-H),8.71- 7.97 (m, 7H), 8.10 (s, 1H, imine N=CH), 7.51,6.74 (m, 4H), 4.45, 4.03 (s, 2H, 2° amide CH2), 2.96 (s, 6H, N(CH3)2). 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 182.60, 169.90, 165.57, 151.78, 144.84, 139.44, 135.14, 133.55, 133.31, 128.85, 128.55, 127.61, 127.32, 126.08, 112.24, 42.60, 41.46.

2.5.4. General Procedure for the Synthesis of Glycine Sulfonamides.

Compound 2a (0.16 g, 0.5 mmol, 1 equiv.) was ground separately with (0.125 g 4-chlorobenzenesulfonyl chloride and 0.123 g 4-methoxybenzenesulfonyl chloride). Then, the mixtures were transferred to a 100 mL round-bottom flask and dissolved in 15 mL (dry DCM). Triethylamine (0.1 g, 1 mmol, 2 equiv.) was added to each mixture. Then stirred at 25°C for 24 h with ongoing TLC monitoring. Pure precipitates of compounds 4a and 4b were attained employing column chromatography with a gradient solvent system of DCM and methanol (100:0–97:3) [31, 32].

2.5.4.1. N-(2-(2-((4-chlorophenyl) sulfonyl) hydrazineyl)-2-oxoethyl)-9, 10-dioxo-9, 10-dihydroanthracene-2-carboxamide (4a)

White precipitate. Yield: 60%; m.p. 245°C (decomposition); FT-IR (cm-1, str.vib.): 3325 (2° amides N-H), 3062 (aromatic C-H), 2935-2812 (aliphatic C-H), 1670 (ketone C=O), 1639 (2° amides C=O), 1589-1477 (aromatic C=C), 1327, 1157 (sulfonamide S=O asym, sym). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.32 (s, 1H, SO2-NH), 10.06 (s, 1H, sulfonamide CO-NH), 9.23 (t, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H, 2° amide N-H), 8.65-7.95 (m,7H), 7.83-7.59 (m, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H), 3.83 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 2H, 2° amide CH2). 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 182.66, 168.33, 165.54, 139.16, 135.21, 133.58, 133.42, 129.46, 127.57, 127.36, 127.33, 126.17, 41.65.

2.5.4.2. Synthesis of N-(2-(2-((4-methoxyphenyl) sulfonyl) hydrazineyl)-2-oxoethyl)-9, 10-dioxo-9, 10-dihydroanthracene-2-carboxamide (4b)

White precipitate. Yield: 65%; m.p. 251°C (decomposition); FT-IR (cm-1, str.vib.): 3282 (2° amides N-H), 3062 (aromatic C-H), 2943-2835 (aliphatic C-H), 1674 (ketone C=O), 1639 (2° amides C=O), 1593-1496 (aromatic C=C), 1330, 1149 (sulfonamide S=O asym, sym). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.20 (s, 1H, SO2-NH), 9.72 (s, 1H, sulfonamide CO-NH), 9.22 (t, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H, 2° amide N-H), 8.65-7.94 (m, 7H), 7.76-7.03 (m, 4H), 3.83 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 2H, 2° amide CH2), 3.87, 3,79 (s, 3H, OCH3). 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 182.66, 165.47, 135.19, 133.58, 133.41, 130.91, 130.34, 127.56, 127.36, 127.33, 126.17, 114.49, 56.03, 41.60.

2.5.5. Synthesis of Ethyl (9, 10-dioxo-9, 10-dihydroanthracene-2-carbonyl) prolinate (1b) [28]

Proline Ethyl Ester HCL (0.8 g, 4.43 mmol, 1.2 equiv.) was dissolved in 10 mL dry DCM in a 250 mL round-bottom flask and stored in an ice bath. Triethylamine (0.75 g, 8.86 mmol, 2 equiv.) was added dropwise over 2 min, and the reaction mixture was maintained at 0°C for 30 min with constant stirring. Anthraquinone-2-carbonyl chloride (compound 1) (1 g, 3.69 mmol, 1equiv.) was dissolved in 30 mL of dry DCM, which was then slowly added to the reaction mixture and stirred at 0°C for 1 h before being refluxed at 45–55°C for 3 h. TLC monitored the completeness of the reaction. After evaporation of the solvent, the residual precipitate was dissolved in 15 mL of ethyl acetate, transferred to a separatory funnel, and washed several times with distilled water, 5% NaHCO3, and 2% HCl. The organic layer was collected and dried. Yellow powder. Yield: 90%; m.p. 131–133°C; FT-IR (cm-1, str.vib.): 3051 (aromatic C-H), 2978, 2885 (aliphatic C-H), 1735 (ester C=O), 1670 (ketone C=O), 1616 (2° amide C=O), 1589, 1489 (aromatic C=C). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.28 (d, 1H), 8.23-8.21 (m, 2H), 8.03 (d, 2H), 7.95 (m, 2H), 4.54 (q, 1H, Chiral C-H), 4.17 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H, ethyl O-CH2), 3.66-3.52 (m, 2H, Pyrrolidine N-CH2), 2.35-1.88 (m, 4H, Pyrrolidine CH2-CH2), 1.24, 0.94 (t, 3H, J = 7.0 Hz, ethyl CH3). 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 182.50, 182.48, 172.01, 167.14, 141.81, 135.21, 135.18, 133.62, 133.51, 132.94, 127.72, 127.33, 125.47, 61.05, 59.51, 49.88, 29.37, 25.39, 14.55.

2.5.6. Synthesis of 1-(9, 10-dioxo-9, 10-dihydroanthracene-2-carbonyl) pyrrolidine-2-carbohydrazide (2b) [29]

Compound 1b (1 g, 2.65 mmol, 1 equiv.) was dissolved in 20 mL of absolute ethanol. Then, hydrazine hydrate 100% (6.33 g, 12.64 mmol, 35 equiv.) was added slowly, and the mixture was refluxed at 70°C for 6 h. TLC ensures the reaction completeness. The solvent was evaporated, and the residual precipitate dissolved in chloroform, poured into a separatory funnel, and washed with distilled water. The organic layer was taken and solvent removed by evaporation to dryness to get a bright orange oily residue, which precipitated by the addition of petroleum ether. Orange powder. Yield: 85%; m.p. 188–190°C; FT-IR (cm-1, str.vib.): 3302 (1° amine and 2° amides N-H), 3066 (aromatic C-H), 2924 (aliphatic C-H), 1674 (ketone C=O), 1627 (2° amides C=O), 1589-1489 (aromatic C=C). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.30 (s, 1H, hydrazide CO-NH), 8.36 (s, 1H), 8.27 (d, 1H), 8.23 (m, 2H), 8.08 (d, 1H), 7.96 (m, 2H), 4.46 (q, 1H, Chiral C-H), 4.26 (s, 2H, Hydrazide NH2), 3.64-3.40 (m, 2H, Pyrrolidine N-CH2), 2.22-1.82 (m, 4H, Pyrrolidine CH2-CH2). 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 182.59, 182.51, 171.23, 167.46, 142.40, 135.16, 135.13, 133.50, 133.48, 133.26, 127.45, 127.29, 125.92, 125.37, 59.75, 50.15, 30.24, 25.31.

2.5.7. Synthesis of (E)-N'-(4-bromobenzylidene)-1-(9, 10-dioxo-9, 10-dihydroanthracene-2-carbonyl) pyrrolidine-2-carbohydrazide (3c) [30]

Compound 2b (0.2 g, 0.55 mmol, 1 equiv.) was mixed with 4-bromobenzaldehyde (0.153 g, 0.83 mmol, 1.5 equiv.). The mixture was transferred to a 100 mL round-bottom flask and dissolved in 20 mL of absolute methanol. Four drops of glacial acetic acid were added, and the reaction mixture was refluxed at 65–70°C for 3 h to obtain a precipitate of product 3c. TLC confirmed the completeness of the reaction. The precipitate was filtered and purified by washing with hot methanol. Yellow powder. Yield: 90%; m.p. 267–269°C; FT-IR (cm-1, str.vib.): 3209 (N-acyl hydrazone N-H), 3066 (aromatic C-H), 2958, 2889 (aliphatic C-H), 1670 (ketone C=O), 1627 (2° amides C=O), 1589 (N-acyl hydrazone C=N), 1558, 1485 (aromatic C=C). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.71, 11.57 (s, 1H, N-acyl hydrazone N-H), 8.30-7.95 (m, 7H), 7.88 (s, 1H, imine N=CH), 7.66-7.13 (m, 4H), 5.41-4.55 (m, 1H, Chiral C-H), 3.76-3.54 (m, 2H, Pyrrolidine N-CH2), 2.46-1.87 (m, 4H, Pyrrolidine CH2-CH2). 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 182.56, 182.51, 172.78, 167.24, 146.19, 142.58, 135.16, 134.11, 133.52, 133.11, 133.00, 132.31, 129.13, 128.65, 127.33, 127.04, 125.50, 59.95, 50.34, 29.46, 25.44.

2.5.8. Synthesis of N'-((9, 10-dioxo-9, 10-dihydroanthracene-2-carbonyl) prolyl)-4-bromobenzenesulfonohydrazide (4c) [31, 33]

Compound 2b (0.2 g, 0.55 mmol, 1 equiv.) was dissolved in 8 mL dry DCM in a 100 mL round-bottom flask and placed in an ice bath. Triethylamine (0.112 g, 1.1 mmol, 2 equiv.) was added slowly, and the mixture was left to stir for 15 min. After that, in 5 ml dry DCM 4-bromobenzenesulfonyl chloride (0.155 g, 0.6 mmol, 1.1 equivalents) was added, and the mixture was left to stir at 25°C for 24 h until the reactions were ensured to be complete in TLC. The resulting crude product was purified using column chromatography with a gradient solvent system of ethyl acetate: n-hexane (0:100 – 50:50). Beige powder. Yield: 60%; m.p. 227°C (decomposition); FT-IR (cm-1, str.vib.): 3329, 3194 (sulfonamide N-H), 3066 (aromatic C-H), 2978 (aliphatic C-H), 1670 (ketone C=O), 1620 (2° amides C=O), 1593-1492 (aromatic C=C), 1388, 1157 (sulfonamide S=O asym, sym). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.42 (s, 1H, SO2-NH), 10.13 (s, 1H, sulfonyl hydrazone CO-NH), 8.27-7.95 (m, 7H), 7.75-7.56 (m, 4H), 4.39 (m, 1H, Chiral C-H), 3.54-3.42 (m, 2H, Pyrrolidine N-CH2), 2.16-1.57 (m, 4H, Pyrrolidine CH2-CH2). 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 182.55, 170.82, 167.20, 142.05, 138.81, 133.52, 133.10, 132.26, 130.38, 127.51, 127.34, 125.78, 59.15, 30.07, 25.08.

2.6. Cytotoxicity Assay

HCT-116 colorectal cancer cells (CCL-247), purchased from ATCC, were cultured in high-glucose medium DMEM supplemented with 10% heated fetal bovine serum, 1% L-glutamine, and 100 IU/mL penicillin–100 μg/mL streptomycin (Euro Clone). Cells were washed with phosphate buffer saline, then detached using 0.025% trypsin-EDTA, centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 10 min, and re-suspended in fresh medium. Cell viability exceeded 90% as determined by the trypan blue exclusion method. Cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 7×103 cells/well and incubated for 24 h at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. Tested compounds prepared from 10 mM DMSO stock solutions and serially diluted to final concentrations of (100, 50, 25, 12.5, 6.25, and 3 μM) (final DMSO ≤0.01%), were added to the wells and incubated for 72 h for each. Subsequently, 15 μL of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) solution (5 mg/mL in PBS) was added to each well and incubated for 3 h to allow Formazan crystal formation. The crystals were solubilized with 100 μL of stop solution. The assay protocol was carried out in three technical replicates for each concentration, and absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a microplate reader [34]. Then the percent cytotoxicity was calculated by using the following equation: Cytotoxicity (%) = C – T/ C × 100, where C denotes the average optical density of control wells and T denotes the average optical density of treated wells. The assay was conducted at Hamdi Mango Center for Scientific Research (HMCSR)/ The University of Jordan.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1. Molecular Docking Study

DNA intercalators and Topoisomerase II (Topo II) poisons exhibit three critical structural features that are fundamental to their function: a planar polyaromatic system, a basic group that can be ionized, and a groove-binding side chain [35]. The rationale behind our molecular design was based on the fusion of anthraquinone with the amino acids proline and glycine, which demonstrated more favorable and additional binding interactions compared to the amino sugars found in anthracyclines, such as the reference compound doxorubicin. Subsequently, various moieties were incorporated to produce Schiff base and sulfonamide derivatives. The resulting scaffolds, functioning as chromophores, were effectively integrated within the groove-binding region and provided enhanced interactions with the Topoisomerase II enzyme and the DNA pocket. These led to improved binding free energy and enhanced interaction profiles. The corresponding docking scores are presented in (Table 1). The root mean square deviation (RMSD) value for the docking of the co-crystallized ligand was 1.918 Å, which validates the accuracy of the docking protocol.

| Compound | Docking Score |

|---|---|

| 3a | -6.167 |

| 3b | -6.878 |

| 3c | -7.836 |

| 4a | -4.379 |

| 4b | -5.535 |

| 4c | -8.734 |

| Doxorubicin | -5.293 |

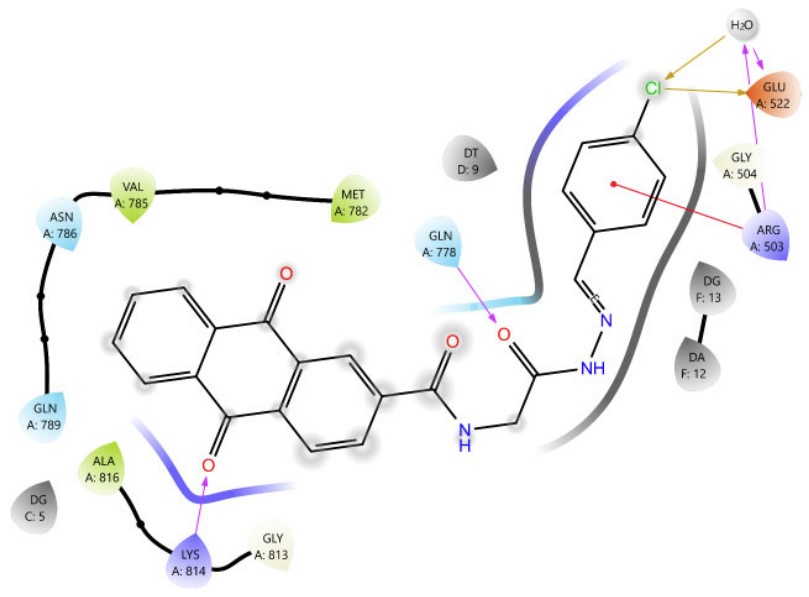

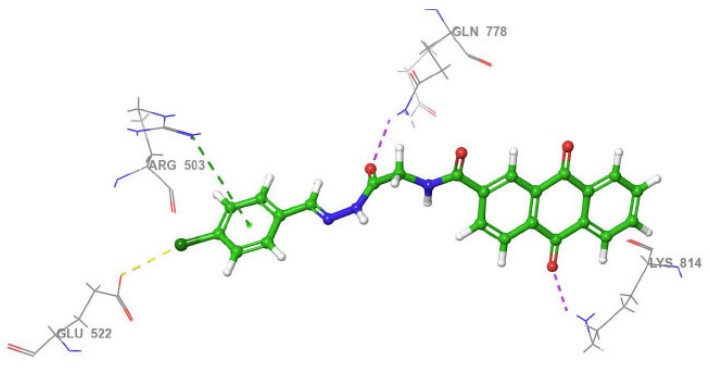

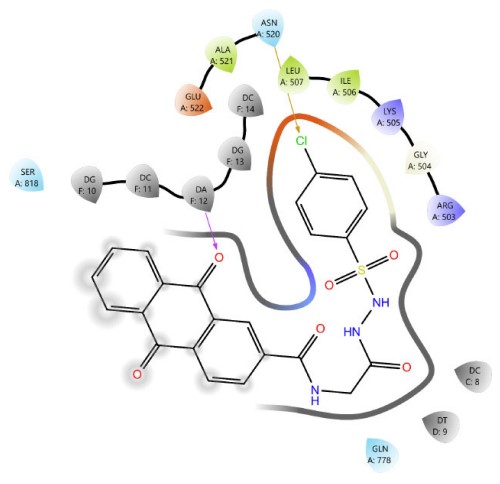

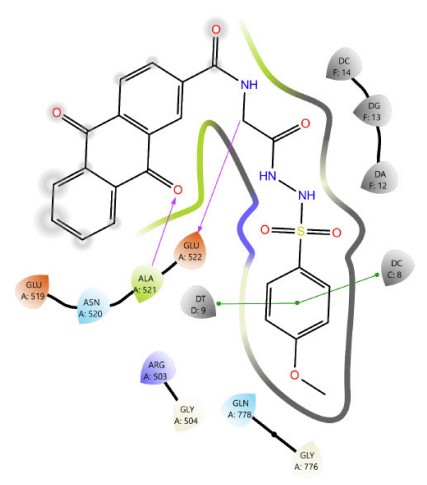

Among Schiff base derivatives, compound 3b is more polar and exhibits a higher docking score; compound 3a demonstrates superior biological activity, which is attributed to its enhanced lipophilicity that facilitates deeper and more efficient penetration into the hydrophobic regions of the target binding site, thereby improving its interaction with the biological target. This observation underscores the critical role of physicochemical properties, particularly lipophilicity, in modulating compound efficacy. Although compound 3a is more polar than 3c, which exhibits a higher docking score, the larger size of the bromine atom in 3c introduces significant steric hindrance, which can obstruct optimal binding interactions and reduce overall biological activity. The observed discrepancy highlights that docking scores alone are insufficient indicators of pharmacological potential, particularly when steric factors and physicochemical properties such as lipophilicity and molecular size play critical roles in modulating target accessibility and compound performance. Thus, compound 3a demonstrates superior activity due to its balanced polarity and reduced steric bulk. The two- and three-dimensional interaction analyses of 3a (Figs. 1 and 2) indicated the formation of hydrogen bonds (H-bonds) with LYS814 and GLN778, a π-cation interaction with ARG503, and a chloride bond with GLU522. Figures 3 and 4 show the interactions of compounds 3b and 3c within the active site.

The 2D interaction diagram of compound 3a against 4G0V.

3D view of the interactions between compound 3a and Topoisomerase II (PDB ID: 4G0V). The purple dotted line represents hydrogen bonding with GLN778 and LYS814; the yellow dotted line indicates a chloride interaction with GLU522 and a water molecule; and the green and blue dotted lines depict π-cation and aromatic hydrogen bond interactions with ARG503, respectively.

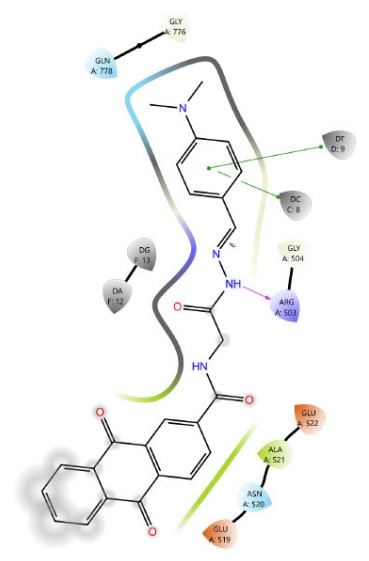

The 2D interaction diagram of compound 3b against 4G0V.

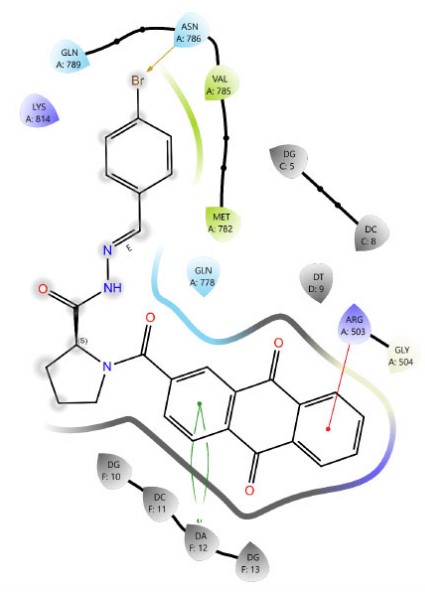

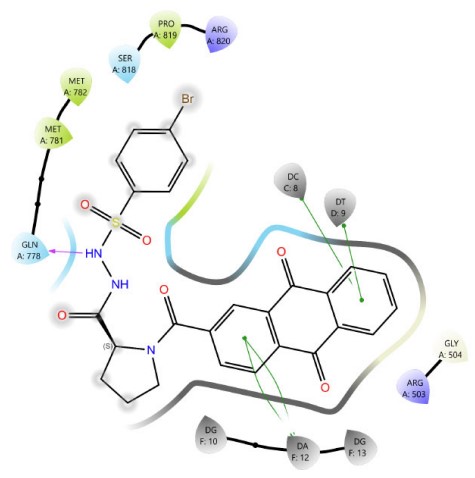

The 2D interaction diagram of compound 3c against 4G0V.

In sulfonamide derivatives, a notable correlation is often observed between molecular docking results and biological activity. Compound 4c, which bears a bromo substituent, consistently exhibits higher docking scores than 4a and 4b, indicating a potentially favorable binding affinity to the target site. However, the actual binding configuration is influenced by several critical factors, including the molecule’s orientation within the binding pocket, the steric bulk introduced by the bromo group, and the spatial distribution of functional groups. These structural characteristics can significantly alter the interaction dynamics, affecting both docking scores and binding energies (Figs. 5-7). Compound 4c (Fig. 7) formed four π–π stacking interactions with DNA bases DC8, DT9, and DA12. It also formed an H-bond between the sulfonamide N–H group and GLN778.

In addition, despite both proline derivatives containing a bromine substituent, proline sulfonamide derivative 4c exhibited superior docking scores and biological activity compared to proline Schiff base derivative 3c, owing to an additional hydrogen bond formed with GLN778 (Figs. 4, 7). These findings validate the critical role of specific functional groups in enhancing molecular interactions and advancing pharmacological efficacy.

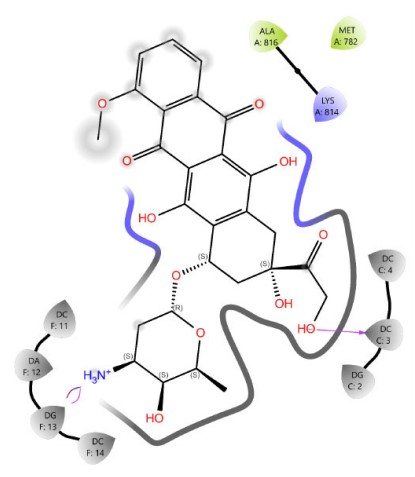

Figures 1, 3–8 depicts the two-dimensional interaction profiles of the final compounds and doxorubicin within the Topoisomerase II–DNA complex (PDB ID: 4G0V), highlighsting key binding residues and interaction types.

3.2. Molecular Dynamic Simulation Analysis

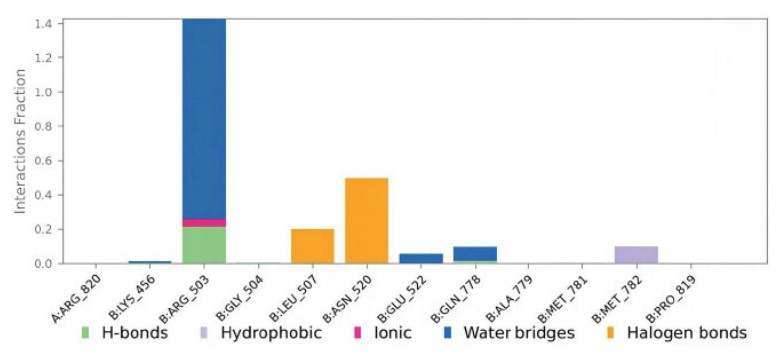

Compound 3a contacts with the protein residues are illustrated in Fig. (9). Values over 1.0 are possible as ARG503 made multiple interactions of the same subtype with the ligand.

3.2.1. Protein-ligand RMSD

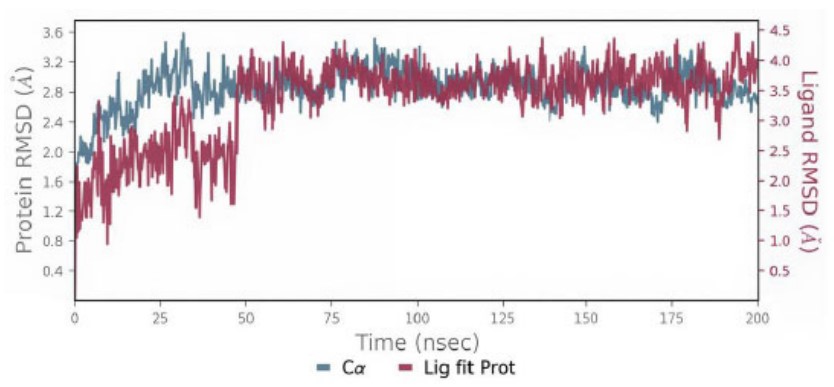

The conformational changes in the protein and ligand from their initial configurations during the simulation were analyzed using root mean square deviation (RMSD). The ligand RMSD result for Compound 3a, illustrated in Fig. (10), remained below 4 Å, indicating acceptable stability of the ligand–protein interaction. This observation is further supported by the dynamic behavior of the complex, which exhibited noticeable fluctuations during the initial 50 ns of the simulation, followed by a stable trajectory with consistent structural integrity throughout the remaining simulation period.

The 2D interaction diagram of compound 4a against 4G0V.

The 2D interaction diagram of compound 4b against 4G0V.

The 2D interaction diagram of compound 4c against 4G0V.

The 2D interaction diagram of Doxorubicin against 4G0V.

A plot of compound 3a contacts with the protein 4G0V residues.

The protein-ligand RMSD of compound 3a.

3.2.2. The Root Mean Square Fluctuation

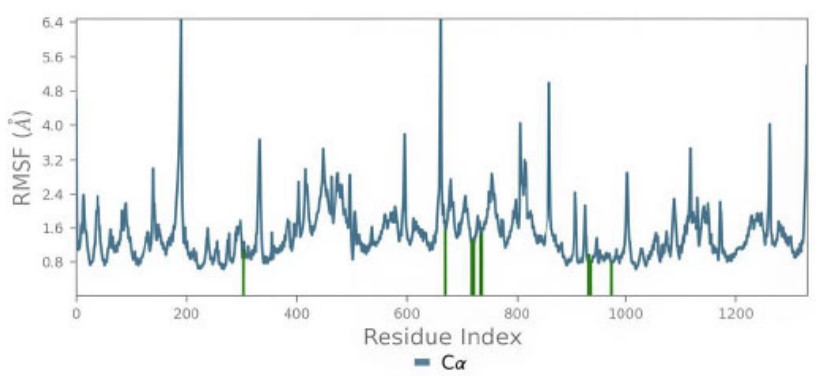

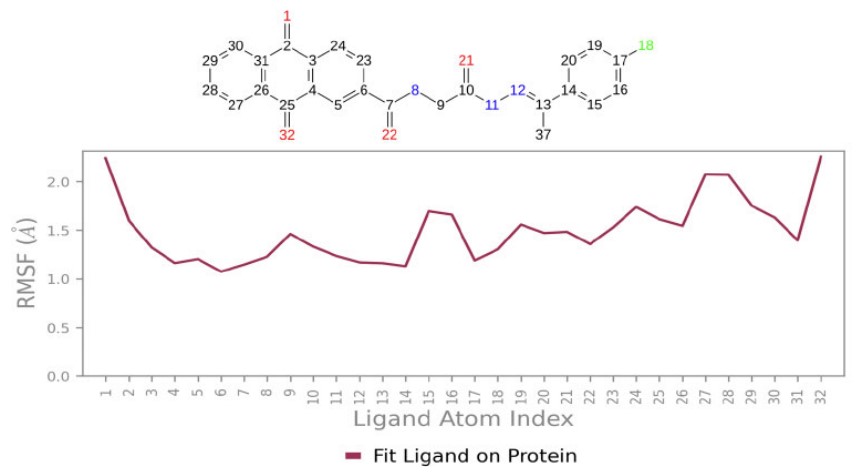

The root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) also provides valuable qualitative insights into the adaptability of residues. Protein RMSF analysis revealed that the interacting residues exhibited fluctuations below 2 Å, offering strong evidence for the stability of the Compound 3a complex with the 4G0V protein. Ligand RMSF below 2 Å also showed well-positioned and tightly bound 3a throughout the simulation (Figs. 11 and 12).

3.3. Pharmacokinetic Properties Evaluation

All compounds adhere fully to Lipinski's rule of five without any violations (results 0, 1), indicating their potential to be considered drug-like, and Jorgensen’s rule of three to be orally active (all compounds with fewer or no violations; results 0, 1). The majority of compounds displayed zero #stars, suggesting their pharmacokinetic profiles fall within the range observed in 95% of established drugs. Moreover, most compounds showed good oral absorption and an acceptable metabolic range. Finally, all of them show a CNS inactivity score of (-2), indicating a low likelihood of their toxicity or harmful effects on the brain (Table 2).

The protein RMSF (Protein residues that interact with the ligand are marked with green-colored vertical bars).

The RMSF of compound 3a with 4G0V

Table 2.

| Compound | #stars | CNS | Human Oral Absorption | Rule of Five | Rule of Three | #Metab |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3a | 1 | -2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 3b | 2 | -2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 3c | 0 | -2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 4a | 0 | -2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 4b | 0 | -2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 4c | 0 | -2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Doxorubicin | 2 | -2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 9 |

Note: #stars: A characteristics that position 95% of the compounds outside the desired features to be drug-like, Normal range: 0-5 (less is better). CNS: Suggest central nervous system activity, (-2 less activity to +2 more activity). The Human Oral Absorption: descriptor indicates possible oral absorption, categorized as 1 (low), 2 (medium), and 3 (high) based on qualitative absorption. The Rule of Five: a value that describes the number of violations of Lipinski’s rule MW< 500 Da, H-bond donors ≤ 5, H-bond acceptors ≤ 10, and a partition coefficient (log P) < 5 (Less than 4, the compound is considered drug-like). The Rule of Three: Counts the violations of Jorgensen’s rule (fewer than three or best to be no violations, suggesting it is orally active. #Metab: shows the number of possible metabolic reactions.

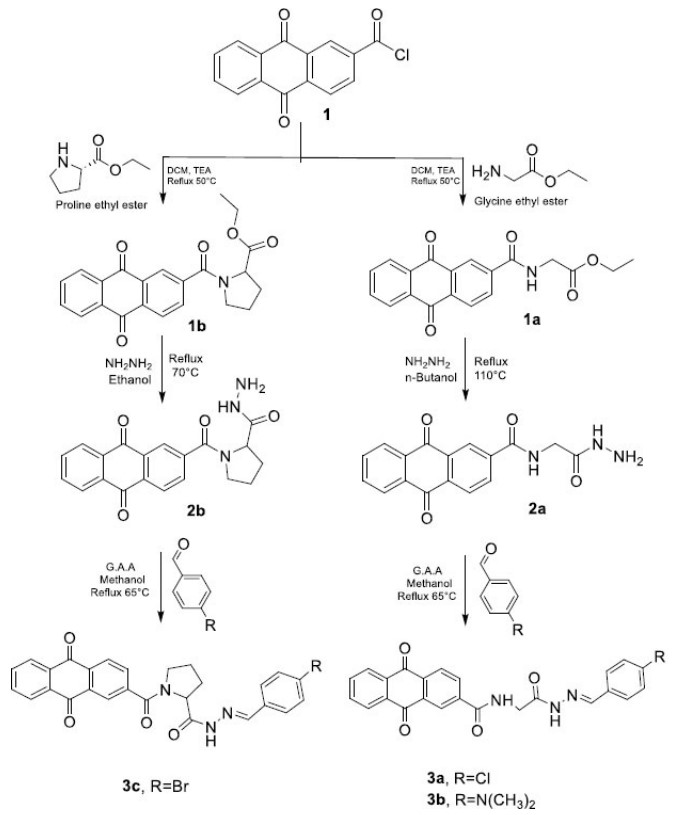

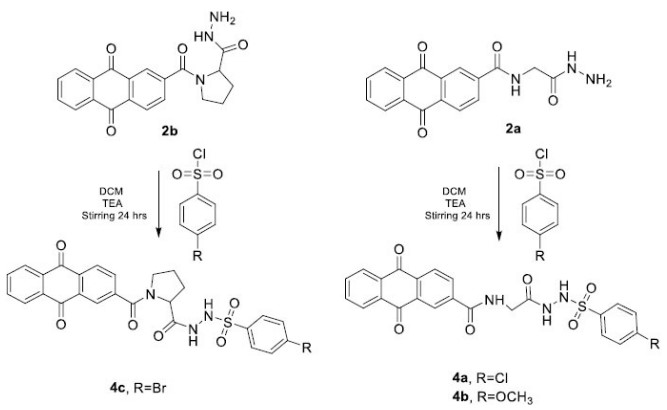

3.4. Chemistry

The synthetic pathway for the target compounds (scheme. 1 and scheme. 2) began with the formation of amides by reacting glycine ethyl ester hydrochloride and proline ethyl ester hydrochloride with anthraquinone-2-carbonyl chloride (compound 1). This reaction was carried out in the presence of triethylamine (TEA), which served as a base to neutralize the hydrochloric acid produced during the process. FT-IR analysis of the resulting compounds 1a and 1b showed the appearance of new bands at 1743 cm−1 and 1735 cm−1, corresponding to ester C=O stretching vibration (str. vib.) in compounds 1a and 1b, respectively. Additionally, bands at 1643 cm−1 and 1616 cm−1 were attributed to amide C=O str. vib. in compounds 1a and 1b, respectively. A new band at 3294 cm−1 observed in compound 1a was associated with amide N–H str. vib. 1H NMR of the compound 1a was characterized by the appearance of an amide proton signal at 9.43 ppm.

Compounds 2a and 2b were then obtained by the hydrazinolysis of glycine ethyl ester and proline ethyl ester, respectively, in n-butanol and ethanol, using an excess of hydrazine hydrate [36]. FT-IR showed the disappearance of ester C=O stretching vibration bands. In addition, the appearance of new broad bands at 3325 cm−1 and 3244 cm−1 in compound 2a, and 3302 cm−1 in compound 2b, was attributed to hydrazide NH–NH2 str. vib. 1H NMR of compounds 2a and 2b was characterized by the disappearance of COOCH2CH3 protons at 4.15 ppm and 1.22 ppm in compound 1a, and at 4.17 ppm and 1.24 ppm in compound 1b, with the appearance of new signals indicating the success of hydrazinolysis of compounds 1a and 1b. The signals were related to NH-NH2 protons at 9.20 ppm and 3.90 ppm in compound 2a, and at 9.3 ppm and 4.26 ppm in compound 2b, all appearing as singlets.

The final compounds 3a, 3b, and 3c were synthesized by nucleophilic addition–elimination reaction via the condensation of compounds (2a and 2b) with various aldehydes to produce Schiff bases, also known as N-acyl hydrazones. Glacial acetic acid was used in this step to ensure proper protonation of the aldehyde, thereby facilitating the condensation reaction. FT-IR analysis showed the disappearance of hydrazide bands at 3325 cm−1 and 3244 cm−1, and the appearance of new bands at 3251 cm−1 and 1612 cm−1, and at 3240 cm−1 and 1604 cm−1, corresponding to the N–H and C=N stretching vibrations of N-acyl hydrazones in compounds 3a and 3b, respectively. Additionally, the disappearance of the hydrazide band at 3302 cm−1 and the appearance of new bands at 3209 cm−1 and 1589 cm−1 correspond to the N–H and C=N stretching vibrations of the N-acyl hydrazone in compound 3c. 1H NMR revealed the formation of compounds 3a, 3b, and 3c through the disappearance of primary amine protons CONHNH2with the appearance of two sets of separated singlets of N-acyl hydrazones, attributed to both the –NHN=C– and –N=CH– protons at 11.63 ppm and 8.01 ppm for compound 3a; 11.27 ppm and 8.10 ppm for compound 3b; and 11.71, 11.57 ppm and 7.88 ppm for compound 3c.

The final compounds 4a, 4b, and 4c were obtained through the reaction of compounds (2a and 2b) with sulfonyl chlorides to form sulfonamides, specifically N-acyl sulfonyl hydrazide. TEA was added to prevent amine protonation and to scavenge the HCl formed during the reaction. ATR-FTIR demonstrated formation of compounds 4a, 4b, and 4c through the disappearance of primary amine and hydrazides bands at 3325 cm−1 and 3244 cm−1 (from 2a), and 3302 cm−1 (from 2b) and the appearance of broad bands at 3325 cm−1, 3282 cm−1 and at 3329 cm−1 corresponds to the formation of secondary amides in 4a, 4b and 4c, respectively. The sulfonyl derivatives 4a, 4b, and 4c were further confirmed by the appearance of absorption bands corresponding to S=O str. vib. at 1327 and 1157 cm−1 (4a), 1330 and 1149 cm−1 (4b), and 1388 and 1157 cm−1 (4c), respectively. 1H NMR revealed the formation of compounds 4a, 4b, and 4c through the disappearance of primary amine protons CONHNH2with the appearance of two sets of separated singlets of sulfonyl hydrazides, attributed to both the –CO-NHNH-SO2- and –CO-NHNH-SO2- protons at 10.06 ppm and 10.32 ppm for compound 4a; 9.72 ppm and 10.20 ppm for compound 4b; and 10.13 ppm and 10.42 ppm for compound 4c (supplementary fig S1-S30).

The chemical synthesis of schiff base derivatives.

The chemical synthesis of sulfonamide derivatives.

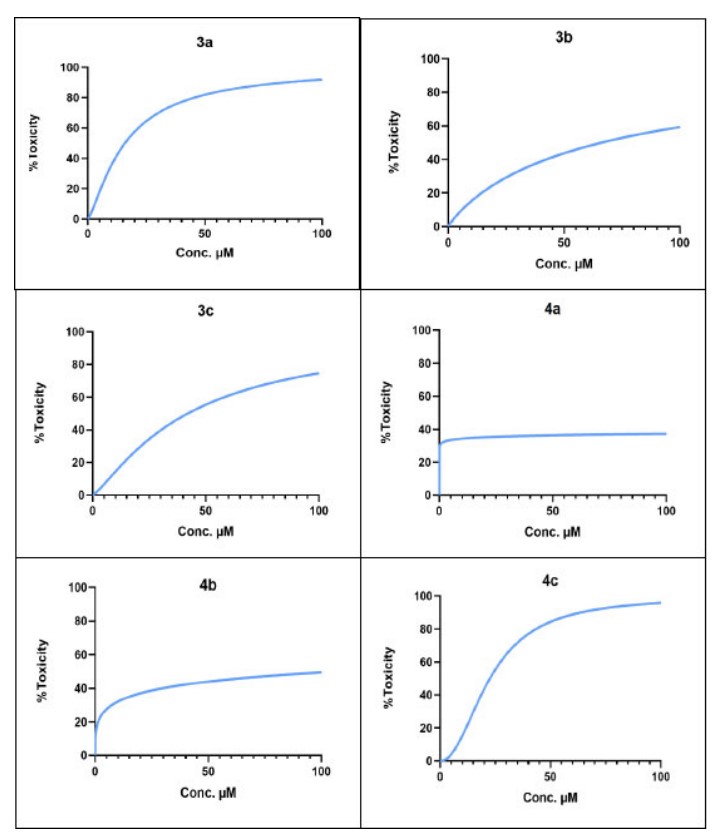

3.5. In vitro Cytotoxicity Evaluation

The study of the cytotoxic effect of different Schiff bases and sulfonamides was performed using the MTT assay of cytotoxicity on the HCT-116 colorectal cancer cell line. Doxorubicin was used as the reference compound due to its structural similarity to the synthesized compounds and its widespread application in chemotherapy; however, Doxorubicin is effective in killing cancer cells at low concentrations, but it is highly toxic to healthy cells at the same concentration [37, 38].

The newly synthesized compounds demonstrated remarkably significant cytotoxic effects, indicating a notable capacity to inhibit cell growth in a concentration-dependent manner (Table 3). Among them, 3a and 4c exhibited promising anticancer activity with IC50 values of 15.85 µM and 22.4 µM, respectively. 3a and 4c exhibit the best interactions with the target, indicating that the docking calculations align well with the experimental data. The concentration-response curve of final compounds (3a, 3b, 3c, 4a, 4b, and 4c) on HCT-116 colorectal cancer cell line is shown in Fig. 13).

4. LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

This preliminary study was limited to in vitro cytotoxic evaluation using a single cancer cell line (HCT-116). The predicted docking and ADME results require further validation through enzyme inhibition and in vivo studies. Future investigations should confirm the mechanism of action and assess selectivity toward normal cells.

| Compound | IC50 (µM) |

|---|---|

| 3a | 15.85 |

| 3b | 66.16 |

| 3c | 42.11 |

| 4a | >100 |

| 4b | >100 |

| 4c | 22.46 |

The concentration-response curve of final compounds (3a, 3b, 3c, 4a, 4b and 4c) on HCT-116 colorectal cancer cell line.

CONCLUSION

In this study, six novel Schiff base and sulfonamide derivatives of anthraquinone were successfully synthesized and structurally characterized by FT-IR, 1H NMR, and 13C NMR spectroscopy. All compounds exhibited favorable drug-like properties, as indicated by acceptable pharmacokinetic profiles obtained through virtual ADME screening. The designed compounds generally achieved superior docking scores and interaction modes than the reference drug, with compounds 3a and 4c scoring -6.167 and -8.734, respectively. Cytotoxicity against the HCT-116 colorectal cancer cell line was evaluated to determine the pharmacological potential of these molecules. According to MTT assay results, these compounds inhibited cell growth in a concentration-dependent manner, as demonstrated by IC50 values of 15.85 µM for 3a and 22.46 µM for 4c. Interestingly, the structures of chlorinated glycine Schiff base (Compound 3a) and brominated proline sulfonamide (Compound 4c) were particularly successful in achieving effective cancer inhibition. Overall, these data reveal that variations in functional groups have a significant influence on biological activity within similar core structures. Therefore, these newly synthesized hybrids may represent exploitable compounds with high therapeutic potential, suggesting a promising novel class of topoisomerase inhibitors. Further studies will involve additional cancer cell lines and enzymatic assays to better explore the cytotoxicity spectrum and clarify mechanisms of action.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSS

It is hereby acknowledged that all authors have accepted responsibility for the manuscript's content and consented to its submission. They have meticulously reviewed all results and unanimously approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| ADME | = Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion |

| ATCC | = American Type Culture Collection |

| CNS | = Central Nervous System |

| DMSO | = Dimethyl Sulfoxide |

| FT-IR Spectroscopy | = Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| HCT | = Human Colorectal Carcinoma Cell Line |

| MTT assay | = (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay |

| NMR | = Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| PDB | = Protein Data Bank |

| RCSB | = Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics |

| SPC | = Simple Point Charge |

| TLC | = Thin Layer Chromatography |

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data supporting the findings of this article are available within the article and its supplementary material files.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the College of Pharmacy, University of Baghdad, and the College of Pharmacy, University of Anbar, for their support.